Steven V. idolized his father, John. After five girls, Steven was the first boy in his family. Steven spent as much time with his father as he could, tagging along at John’s workplace, Baca Auto on S. Main St. in Belen.

Even when Steven got in trouble and his mother told John that the boy needed a whipping, John would take Steven into a room, “whip” him with a handkerchief and tell the boy to “yell” as if he was in real pain.

But then things went terribly wrong. By the time Steven was 16, he had gotten into so much trouble that he was sent to the New Mexico Boys School at Springer, a correctional facility for at-risk boys from across the state.

What had happened to cause this sudden change in Steven’s life? What did he experience at Springer? And what impact did his year and a half in custody have on the rest of Steven’s life?

Joining the Wild Ones

After working long hours at Baca Auto, John worked as a security guard at Tabet Hall, Belen’s favorite dance hall in the 1950s and early 1960s.

On Oct. 7, 1961, he came home tired, went to bed and never woke up. He had died from a massive heart attack at the age of 47. Steven was only 13.

Missing his father’s love and attention, Steven got into more and more trouble at home, in school and on the streets of Belen. As a teenager, he joined the Wild Ones, a tough gang that fought rival gangs, especially gangs from Los Lunas.

Gang fights and individual run-ins led to serious injuries. Steven was hit in the head with a tire tool. Steven resorted to stabbing another boy over a girl, leaving an “H” shaped scar on the boy’s side that remained visible for the rest of his life.

By the time he was in the eighth grade, Steven cut school nearly every day. He routinely wrote excuses and had an older sister sign them for him.

Steven was sent to the “D” (delinquent) home for 90 days in 1963. Once back home, he continued to skip school until the day a truant officer caught him down by the railroad tracks. The officer brought Steven into his office and was about to give the boy a lecture when Steven slapped the man in the face and ran off.

Alerted of the incident, Belen police officers soon picked Steven up. He apologized for his misbehavior but was sent to court and sentenced to the New Mexico Boys School in Springer. He was to remain at Springer until he was 21 years old or until he was released by court order.

Arriving at Springer

Founded in 1909, the New Mexico Boys School, better known as simply “Springer,” had earned a reputation as a brutal institution where only the most incorrigible juveniles were sent. Sadly, Springer was a busy place in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Belen and many other communities across the United States suffered from a wave of juvenile delinquency, identified, along with polio and the threat of nuclear war, as one of the greatest concerns to most Americans.

Photo courtesy of the Center for Southwest Research, Zimmerman Library, University of New Mexico

Boy and counselor, New Mexico Boys School, Springer.

Steven arrived in Springer and, like all new boys, was placed on 90 days of lockup. This meant that Steven and his fellow inmates were locked in 8-foot by 5-foot cells 24/7, with the exception of meals and one hour in a sparse rec room each day.

Conditions were so bad that Steven planned to escape. He went so far as to bundle his clothes and drop them outside through the bars of his cell. He only changed his mind because he didn’t want to be sent into isolation if he was caught.

After serving his 90 days, he was transferred to a dorm with other boys his age. He cooperated well enough to be given a choice of whether he wanted to transfer to a camp near Eagle Nest or remain in the dorms for the duration of his sentence. Steven chose the camp.

Life in Camp

Steven’s new facility was an honor camp about 50 miles northwest of Springer. With no cells or fences, it was not unlike the adult honor farm north of Belen, in Los Lunas.

Boys were required to follow the camp’s rules and not try to escape, for fear of being sent back to Springer. Run much like an army camp, the boys were responsible for making their cots, washing their clothes and standing for inspection every day but Sunday, when they were able to attend a Catholic mass.

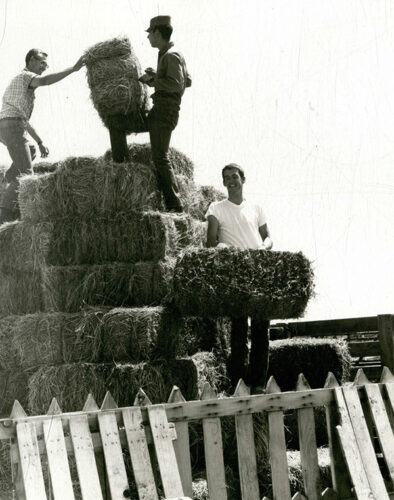

Photo courtesy of the Center for Southwest Research, Zimmerman Library, University of New Mexico

Boys at work, New Mexico Boys School, Springer.

The boys’ days began at 6 a.m. After breakfast and inspection, they policed Cimarron Canyon for trash or worked on local farms or ranches each morning. They attended classes taught by local teachers each afternoon. Steven made progress on completing his high school diploma.

Meals were decent, except for a few items on the menu, especially lima beans. Steven learned to stash the hated lima beans into his pockets and empty them into a fish pond after meals. Lights went out at 10 p.m. sharp.

Boys at the Eagle Nest camp were brought into Cimarron once a month to watch a movie in the small town’s theater. Steven could have visitors once a month. His mother and the girl he fought for in Belen often came by to visit, sitting at picnic tables or taking short walks down forest trails. His mother and girlfriend often brought much-appreciated care packages to last him through the month.

A majority of boys followed the rules, knowing that serving their time at the open-air camp was far better than conditions back in Springer. But there were boys who seemed unable to avoid trouble. Some went AWOL. Others were caught with liquor, ironically left by the side of a road by their parents.

Steven and most boys kept their noses clean and adjusted to their environment. They especially adjusted well under the guidance of effective adults who lived in camp, not as guards but as advisors.

Steven was fortunate to have a Mr. Pompey as his “house parent.” Steven remembers Mr. Pompey talked to him man-to-man about what to expect in life. He taught Steven he had to respect others before they would respect him and, most important, he taught the young man to respect the law, first in camp and then in society.

Evaluations were held to discuss each boy’s progress. There were no demerits and no “good time” offered for staying out of trouble. Progress was all that mattered in each boy’s case history.

Apparently, Mr. Pompey and other adult supervisors believed Steven had made sufficient progress to be eligible for early release. After a year and a half, the court released Steven and allowed him to go home to Belen in 1964.

Steven now remembers his time at the Eagle Nest camp as a good learning experience, a place where he first experienced life on his own; where he learned discipline to finish projects and how to follow instructions and obey rules.

He also learned three other parts to adulthood: responsibility, respect and patience.

He learned all this without undue stress or any signs of post-traumatic stress disorder that other boys experienced at Springer. In fact, after returning home, Steven told his mother his 18 months away were the best thing that had ever happened to him in his young life.

After Springer

Shortly after Steven’s release from Springer, he was drafted and sent to boot camp in Ft. Bliss. He served his two-year hitch at Ft. Bliss, serving as a baker for new recruits, many of whom were headed to Vietnam at the height of the war in Southeast Asia, 1967-69.

Photo courtesy of the Center for Southwest Research, Zimmerman Library, University of New Mexico

Boys at play, New Mexico Boys School, Springer.

Did Steven live happily ever after his time at Springer? Unfortunately, he did not. He went AWOL while in the Army, heading home for Christmas without permission. MPs came for him in two days. Under the Army’s Article 15, he was restricted to Ft. Bliss and given extra duties for 14 days as his punishment.

Steven’s life did improve over time, especially when he applied what he had learned at the Eagle Nest camp. He married the girl he fought over in high school and who came to visit him with care packages at his Eagle Nest camp.

Together, they raised two fine boys who never got into serious trouble. Steven got a steady job, became a valued supervisor and retired after more than 29 years of able service. He is a leader in his local church and does part-time work just to keep busy in retirement.

Steven is justly proud of how he turned his life around. He gives credit to his wife, his good friend, Jose, his church and his employers. He also gives credit to his year and a half at Springer and its Eagle Nest camp, where he learned so much about becoming an adult and taking responsibility for one’s actions — both good and bad.

There are many stories about the hardships boys faced at Springer, but the institution underwent several major changes by the mid-1960s, including the creation of its Eagle Nest camp with its able advisors, including Mr. Pompey.

Stephen V. was fortunate to arrive at Springer at just the right moment in the school’s long history. He became one of the school’s success stories, surviving to lead a happy, productive life while many of his old friends continued down the wrong path, a path that often led to the state pen and, in some cases, the horrific, deadly Santa Fe prison riot of 1980.

(La Historia del Rio Abajo is a regular column about Valencia County history written by members of the Valencia County Historical Society since 1998.

All names in this installment of La Historia are fictional.

Opinions expressed in this and all columns of La Historia del Rio Abajo are the author’s alone and not necessarily those of the Valencia County Historical Society or any other group or individual.)

Richard Melzer, guest columnist

Richard Melzer, Ph.D., is a retired history professor who taught at The University of New Mexico–Valencia campus for more than 35 years. He has served on the board of directors of the Valencia County Historical Society for 30 years; he has served as the society’s president several times.

He has written many books and articles about New Mexico history, including many works on Valencia County, his favorite topic. His newest book, a biography of Casey Luna, was published in the spring of 2021.

Those interested in joining the Valencia County Historical Society should contact Dr. Melzer at [email protected].