La Historia del Rio Abajo

Early New Mexicans standing on the crests of the Manzano Mountains looking to the east would have beheld a much different view than you do today.

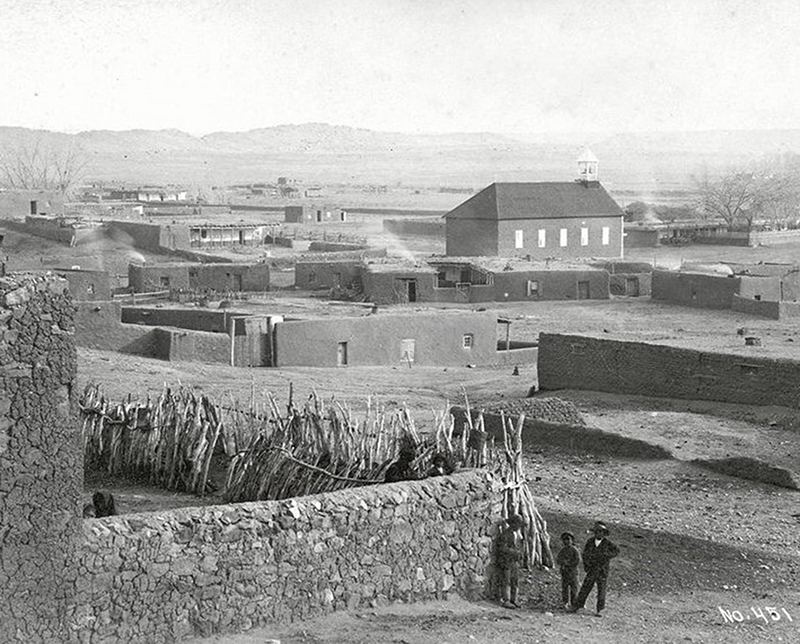

Submitted photos

Galisteo looking east in 1880.

There, laid out before them, would have been a vast lake system. The water levels in these lakes, now called Lake Estancia and Lake Willard, waxed and waned over the millennia — sometimes being as deep as 400 feet and sometimes being completely dry.

The valley had no outlet, so runoff from melting snow pack would fill the lakes during the spring, and the hot run would evaporate some or all of the water during the summer, leaving a layer of salt covering the valley. As the glaciers retreated from North America at the end of the last Ice Age (circa 10,000 BCE), evaporation exceeded runoff, and Lake Estancia and Lake Willard essentially disappeared, leaving deep layers of salt.

The Native Americans who occupied New Mexico before the first Spanish invaders recognized the value of salt. Not only was the mineral useful as a seasoning, but it was necessary for preserving meat, tanning hides, use in religious rituals, and necessary for making some pigments. In fact, the Zuni people consider their salt flats as a sacred origin location, which they refer to as Ma’l Oyattsik’i, sometimes translated as “Old Lady Salt” or “Salt Woman.”

Pueblo villages

Arrowhead evidence suggests that as early as 15,000 years BCE people lived or camped along the shoreline, hunting giant sloths and bison and perhaps fishing for the cutthroat trout that lived in the creeks and shallows of the lakes.

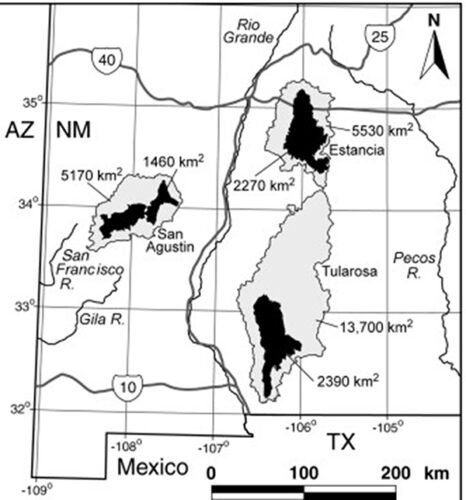

Ice Age lakes in New Mexico — black represents lakes, shaded area represents drainage basins.

Villages started to develop on Chupadero Mesa along the eastern face of the Manzano Mountains overlooking the Estancia Valley about 600 AD. These villages, which started out as groups of pit houses and eventually graduated to stone architecture, ran from what is now Chilili on the north to Gran Quivera, on the south.

In the late 13th and early 14th centuries AD the villages had consolidated into large, Pueblo-style villages in Abo Canyon and on the south end of the valley, with the three most prominent pueblos being what we now know as Gran Quivera, Abo and Quarai.

In addition to routine agriculture, the residents of these Pueblos learned to harvest and purify the salt. Native Americans from the Rio Grande Valley — the Jumanos area and the Plains — came to get salt, and traders from the Pueblos carried the salt as far north as Taos and as far south as Chihuahua.

The Spanish arrival

Although the 1540 Francisco Coronado expedition did not discover the salt lakes east of the Manzanos and their associated pueblos, the 1581 Chumascado expedition visited them and brought a sample back to Mexico City, describing the salt as “the best discovered by Christians.”

Not long after the “discovery” of the salt lakes by the Spaniards, Franciscan missionaries came into the area to “Christianize” the Native Americans. Churches were built at Chilili (Nuestra Senor de la Natividad, 1610), Abo (San Gregorio, 1626), Quarai (Nuestra Senora de la Purisima Conception, 1627), Gran Quivera (Iglesia de San Isidro, 1630, and San Buenaventura, 1660), as well as others such as Pueblo Blanco, Pueblo Colorado, Frank’s Pueblo and Pueblo Pardo.

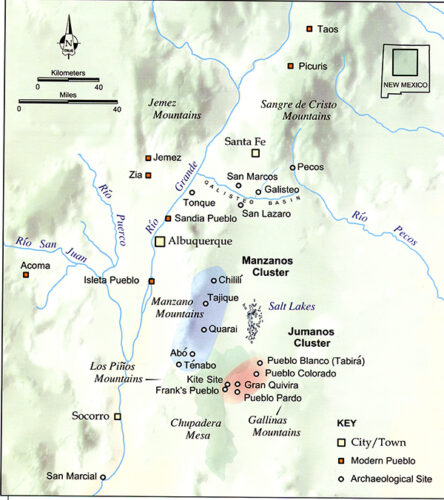

Occupation of the salt lakes area in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Conversion to Christianity was not a process readily accepted by the Native Americans. In most cases, the Franciscans forbade native religious practices and burned kivas and relics, such as masks and kachinas.

Religious exploitation was not the only burden imposed by the Spaniards. The arrival of the Spaniards meant that the need for salt increased dramatically, particularly since it could be used to remove silver from the silver ore being mined in northern Mexico. In fact, Gov. Bernardo Lopez de Mendizabal (1659-1661) shipped wagon caravans of salt to the silver mines of Mexico, nearly 700 miles to the south.

As a part of their reward for becoming Christian, many of the natives from the pueblos around the salt lakes were forced to carry salt for their new overlords. One Franciscan friar noted that the governor cared little for the safety and health of the Indians.

He explained that the burdens of transporting this precious commodity, largely in baskets on individual’s backs … had occasioned among the natives serious illness and convulsions, some of them being permanently incapacitated … both on account of the haste and the misfortunes attending their departure and the long distance which they carried the salt.

Times and conditions took a turn for the worse for everyone in the late 1660s. A prolonged drought led to widespread starvation, and raids from Apache Indians were endemic. To add salt to the wound (pun intended), an epidemic struck the area in 1671, killing both people and livestock. The survivors of these plagues abandoned their homes, opting to live with their linguistic cousins in the pueblos of the Rio Grande Valley.

The Native Americans who left the area in the 1670s did not return, so the Salt Lakes were left undisturbed until the return of the Spanish in the early 1700s after the end of the Pueblo Revolt.

Although the area remained largely abandoned by permanent residents for nearly 150 years, the demand for salt did not go away. The precious commodity was used to preserve buffalo hides and beaver pelts and to pickle various foods, such as buffalo tongues so that they could be shipped in the days before refrigeration.

If anything, salt increased with the increasing population of New Mexico. Sheep husbandry was a major source of income, particularly in the Rio Abajo. Range sheep required about a quarter ounce of salt per day, so the ricos with enormous herds (50,000 to 100,000) needed large quantities of the previous material.

Governors would secretly organize caravans to the salt lakes once or twice a year under heavy military escort, sometimes even with cannon. The caravans would leave from Galisteo, reaching the Estancia Valley after about a three-day journey.

Some workers would rake lower quality salt (sometimes referred to as black or brown salt) from the edges of the lake, while others would wade into the brine to get the fresher, purer white salt. After a few weeks of hard labor, when the oxcarts were full, the caravan would return to Galisteo. From there, the salt would be distributed up and down the valley, selling for as much as $1 a bushel (about $30 per bushel in today’s dollars).

In addition to being used for cooking and food preparation and preservation, salt became a cultural symbol. Mothers would throw a pinch of salt onto the embers of a fire before retiring for the night. This was done to prevent flying witches from coming down the chimney.

Others would go out into a thunderstorm and toss a handful of salt into the air in the sign of a cross while praying, “Santa Barbara, libranos de rayos.” (Santa Barbara, protect us from the lightning. Santa Barbara was the patron saint invoked to prevent danger from thunder, lightning, violent death at work or explosions of gunpowder.)

End of salt mining

During the Mexican period (1821-1846), the caravans continued, although the threats from Apache raiders also continued. At least part of the complex of salt lakes in the Estancia Valley was granted to Antonio Sandoval as the La Salina Grant by Gov. Manuel Armijo during his second or third term as governor between 1837 and 1846.

Despite some fraudulent claims from Texans, who still coveted New Mexico as their own, in 1854, the territorial Legislature passed a law that all citizens could harvest the salt for free. However, with the coming of the railroad in 1879, the demand for salt from the lakes decreased, although the demand for the lower quality salt for livestock continued well into the 20th century.

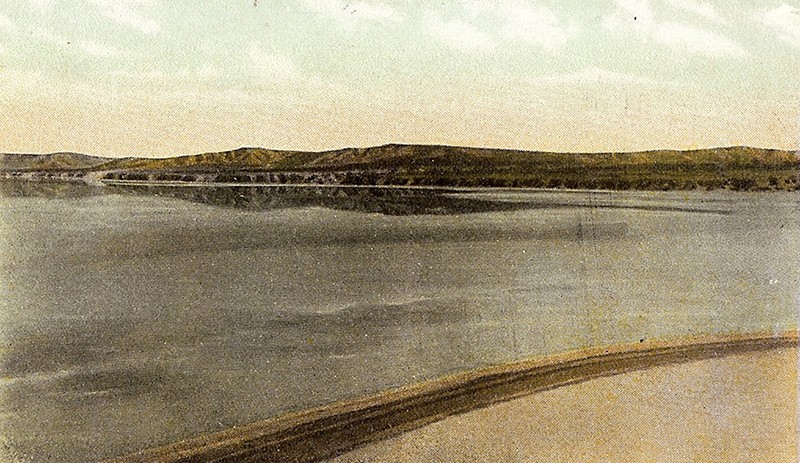

A postcard from the early 20th century showing New Mexico’s “Great Salt Lake.” The railroad tracks are in the foreground.

Later, owners of all or part of the La Salina Grant included the New Mexico Fuel and Iron Company, the Willard Salt Lake Refining Company and a number of private individuals.

The death knell for salt recovery came in the 1930s with the opening of potash mining operations in Carlsbad. Salt is an abundant and inexpensive by-product of potash mining and so the Estancia Valley salt operations shut down after nearly 600 years of operation.

Today, if you travel east on US 60 about 15 miles west of Mountainair, you can see one of the remaining salt lakes and imagine how the area would have appeared when the valley was full of water and when primitive, but large-scale, salt recovery operations were in full swing.

(La Historia del Rio Abajo is a regular column about Valencia County history written by members of the Valencia County Historical Society. The author of this month’s column is John Taylor, a retired engineer from Sandia National Laboratories and board member of the Valencia County Historical Society.

He is the author or co-author of 19 books on New Mexico history, including “Murder, Mystery, and Mayhem in the Rio Abajo,” “A River Runs through Us,” “Tragic Trails and Enchanted Journeys,” “Mountains, Mesas, and Memories,” and “Years Gone by in the Rio Abajo,” all co-edited with Dr. Richard Melzer.

Opinions expressed in this and all columns of La Historia del Rio Abajo are the author’s only and not necessarily those of the Valencia County Historical Society or any other group or individual.)