LOS LUNAS — Guardians of the record. That’s another — albeit, heroic name — for court reporters.

The people who, during a court of deposition proceeding, write down every word spoken by every person during a hearing in front of a judge.

“Part of my responsibility is to make sure that everything is accurate and make sure that everything is spelled correctly,” said Margaret “Margo” Gurule, court reporter for 13th Judicial District Court Judge Cindy Mercer in Los Lunas. “I often have to look up stuff like — I was just working on a medical malpractice case and I never heard the word mesenteric ischemia.

“So, if my computer doesn’t recognize my strokes as being that, it’s going to come up in steno.”

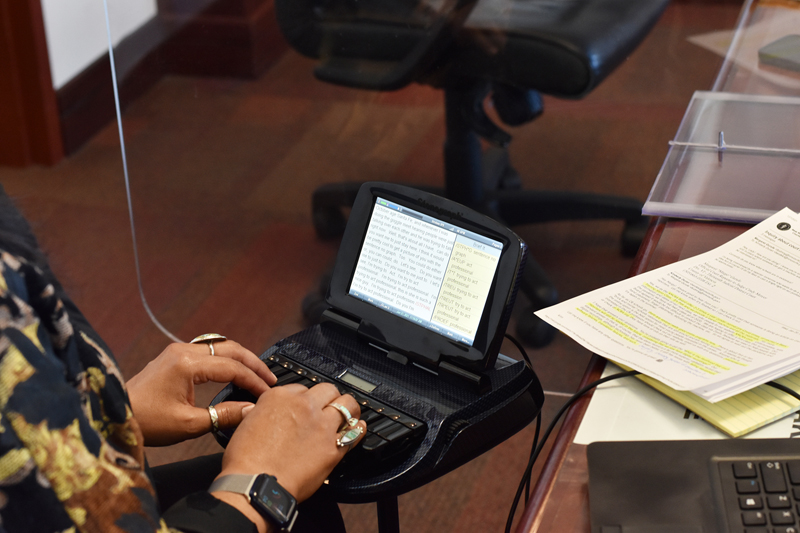

Matthew Narvaiz | News-Bulletin photos

Margaret “Margo” Gurule looks at her transcripts after typing out an interview she did with a Valencia County News-Bulletin. Gurule is the court reporter for 13th Judicial District Court Judge Cindy Mercer.

Gurule has been doing this job for some time now, dating back to the late 1980s. In part, she says her job is simple: transcribe the conversations happening in the courtroom verbatim, no exception.

If, for instance, the courtroom has noise that isn’t someone’s spoken word, Gurule’s job is to ignore that and instead put forth all her focus on the words she hears people uttering.

If people are speaking over one another she, as well as the judge she works for, can bring order to the court so that the transcriptions being taken by Gurule aren’t tampered with.

“People generally speak at a gettable rate, but people come in here and talk really, really fast, and then it requires concentration, focus,” she said. “I’ve been known to ask people to slow down because I’m responsible for this.

“If things are getting away from me, if people are talking over each other, that makes it really difficult. My judge is very good about keeping order; she’s like, ‘Don’t interrupt, let them finish talking and then you have your turn.’”

Gurule says Mercer conducts the courtroom in a very orderly fashion, and she really appreciates that because it makes her job easier.

“Some people can talk as fast as … 300 words a minute but it’s usually not for extended periods of time so you can catch up,” Gurule said. “You know you can hold on, if you will, but it takes a lot of focus.”

A court reporter’s job of transcribing isn’t done via computer, it’s done with a machine called a stenotype, which is a computer-like machine that has a screen and a series of keys — less than that of an alphanumeric keyboard — which are pressed together to create a series of words.

On the bottom of the stenotype keyboard are the normal vowels in the alphabet, and on the second and third levels of the keyboard are a combination of keys that are pressed together to create a word or letter.

Stenotype machines have come a long way since its creation in the 1930s. Nowadays, a combo of letters that a court reporter types can create an entire word. The definition for this practice is called brief form.

“There’s a theory, which consists of all vowels and consonants, and you don’t have all your consonants, you have an A, O, E, U,” Gurule explains. “For example, all these keys pressed together form the long I sound, A and O together form this short I sound.

“You use combinations of consonants and vowels to form, phrases, words. There’s a lot of things called brief forms. I write ‘considered’ just by writing the K and the R. I write ‘seriously’ just by writing S and L. So here’s lots of brief forms.”

The stenotype machine is a way for court reporters to type quicker. In a courtroom, court reporters, such as Gurule, use these machines so they can type every word spoken during a court hearing.

Outside of the courtroom, Gurule still has a job to do. If she isn’t transcribing a court proceeding, she’s organizing her calendar of events for the upcoming days, weeks and months.

She’s also going back to prior transcripts and editing them for clarity by correcting spelling and punctuation, so if someone — for instance a lawyer — asks for those transcripts, it isn’t a jumbled mess of words they receive.

Court reporters still have it tough even though they are able to type in shorthand. Each state has a different required word-per-minute count, and many get frustrated by that number and don’t continue with earning their certificate from an accredited school. In New Mexico, the goal is to type 225 words per minute.

So many words are being typed so fast and in such long succession that by the end of a trial, Gurule says she can have as many as 35-40 pages per hour worth of transcripts.

With the pandemic in the mix, Gurule’s job has changed up a bit — but not enough to where she needed to make sweeping changes to how she works.

For instance, instead of people in the courtroom, hearings are now being conducted via Google Meet. If someone speaks over another, that person is muted so that Gurule can continue to get her job done.

There’s also audio recording software, too, that has been introduced over the years and acts as a tool to go back and make slight edits to transcripts.

Getting into a niche job

Gurule is aware of the unusualness of her job and how hard it can be, too. She said people who try to go to school for this job end up leaving out of frustration.

Those who stay and complete their certificate are opened to a world of endless possibilities.

“You can work as hard as you want to,” Gurule says.

Having graduated from Los Lunas High School, Gurule was first introduced to court reporting in the classroom. She found the job interesting and, from there, made it her mission to find her place in this field of work.

At 18 years old and undisciplined in the art of court reporting, Gurule attended International Business College in Albuquerque in the late 1980s and received her certificate.

Gurule also had the help of a mentor, Viola Aragon, who was a court reporter herself for the 13th Judicial District Court back in the day.

“She basically made sure that I went to school, made sure that I practiced and made sure that I passed my test,” Gurule says.

The school no longer exists — and there are about five or six brick and mortar schools for court reporting left in the country. With the pandemic in the mix, schooling can be done online and is more easily accessible to attain a certificate than ever before.

When Gurule received her certification, she worked for Paul Baca Court Reporters in Albuquerque for 13 years before starting a firm with someone else from 2001-2005.

Then she left New Mexico and went out for a new adventure that landed her in California, where she freelanced and even worked for several different firms in a span of nine years. Working out of the San Francisco area, Gurule freelanced for many companies and local governments.

“I worked for premeds firms, I worked for Merrill Corporation. I worked for Atkinson Baker. I did pro tem work in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California in San Francisco,” she said. “I did pro tem work for the district courts in the county of San Francisco. I was a freelancer.”

What brought Gurule back was, at its heart, New Mexico itself. It also helped that a friend of Gurule’s mentioned that a new judge was on the bench and in need of a person such as her.

However, it was really being closer to family and friends that acted as a motivator to return to the Land of Enchantment.

“New Mexico, for me, is very comfortable and comforting and it’s like a little nest — it’s like, I know I have a lot of family here, I have a lot of friends,” Gurule said. “I always tell people we call it the Land of Entrapment for a reason, because you’re either born here and you never leave or you come here and you never leave.”

Gurule wants to see others — younger people — take an interest in this sort of work. She says the skills you can learn by being a court reporter in a courtroom is endless.

“People don’t get intrigued by this, but it really is a fascinating job. You learn about medical terms, you learn about business terms, you learn about construction, sometimes you learn about police procedures and you learn about the criminal mind,” Gurule says. “I think I’ve learned a lot throughout the course of my years.

“I just think that it’s a great job … I never thought I wanted to be in court and now I can’t imagine myself being anywhere else.”