Being in school has never been more complicated.

With the COVID-19 pandemic closing schools in March, education across the state was disrupted as districts pivoted to remote learning.

What started as an extended spring break has now become the cliched “new normal,” and it is far from ideal for many Valencia County families.

Whether it’s issues with technology, frustrations over receiving timely services such as IEPs, communicating with teachers or the myriad of other challenges, everyone agrees the situation is less than ideal.

Gloriann Gurule has two children in Belen Consolidated Schools — one in the fourth and the other in the eighth grade. While they do remote learning, she is able to stay at home with them, but finds herself challenged in a way most parents aren’t. As a deaf parent, Gurule says her biggest struggle is vocabulary.

Jovanna Gurule, an eighth-grader in Belen Consolidated Schools, and her brother, Richard, in the fourth grade, work on lessons from home.

Submitted photo

“Both my children are hearing. I have trouble with how to vocalize. I can sign or draw with ASL (American Sign Language) but it is difficult to help them with assignments at times,” Gurule said.

Gurule said lessons can be hard without having a teacher readily available.

“My son is really social and during Zoom meetings; he’s a question asker. After though, he will come up to me with a question and sometimes he’s not sure how to ask it,” she said.

Her son also has an Individualized Education Program, which hasn’t been finalized, something she hopes will happen by the spring semester.

“I wish he had more resources. He can ask his teacher a lot of times but right now, everything is up in the air,” she said.

The mother of sixth-grade twins, Angela Cano said she’s been lucky enough to be able to send her sons to the Belen Community Center on the days they are learning “at home.”

“They have computers there and a substitute teacher to help my kids learn while I’m at work,” Cano said. “You know two 11 year olds are not going to work on their own.”

At this time, the program at the community center is at capacity.

Her sons are in class at Central Elementary on Thursdays and Fridays, where they are maintaining straight As, and their teacher calls Cano on Wednesdays to check in.

“The teachers are really good and communication from the school is really good,” she said. “I really wish the district would have given everybody laptops. Even if they did, I would still want them at the rec center.”

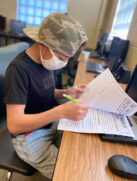

Gonzalo Cano, an 11-year-old sixth-grader at Central Elementary School in Belen, works on an assignment during remote learning. He spends remote learning days at the Belen Community Center while his mother, Angela Cano, is at work.

Submitted photos

Since last spring, BCS has spent $1.2 million on software and hardware for teachers and students and is still behind the curve, said recently retired BCS Superintendent Diane Vallejos.

“We don’t have funding sources such as HB 31 like other districts do, so we are behind technology wise. We’re at a better place than we were last spring,” Vallejos said. “But it isn’t ideal. We know that.”

HB 31 is legislation that has been in place for decades that allows a local school board to enact a tax to fund technology purchases.

Like many districts in New Mexico and across the country, BCS is still waiting on devices it ordered months ago. There are the 300 Dell laptops that were promised by Aug. 28 that are still back ordered. The district has received donated laptops and other devices, as well as items such as 75 hot spots purchased by Socorro County to bring internet services to students in the southern part of the district.

The district is also fighting for its share of hot spots provided to the state by T-Mobile, Vallejos said. Of the 12,000 devices awarded to New Mexico, Albuquerque Public Schools has asked for 6,000 of them.

“I asked them for whatever we can get,” she said. “I was told they could possibly get us 10 or 20. I’ll take three, four, whatever you got.”

The district did receive $1.2 million in CARES Act funding in May, which could be split 50/50 between technology and COVID-19 related purchases, such as cleaning supplies and PPEs. However, the state took 41 percent credit for the funding, Vallejos said, which meant the district didn’t have the actual cash in the bank.

“The state took credit for about $600,000, which meant we had to go find that somewhere else,” she said. “I know people would have liked to see us move faster on some of those purchases, but it’s a hard call to make to say we’re going to spend $1.2 million not knowing if we actually have it.”

Setting aside the technology challenges, Vallejos said she and everyone at the district are aware of the toll the situation is taking on students and parents alike.

“I took a call from a parent. She’s worked really hard in her life to get where she is. She dropped out of school and wants to make sure her kids don’t,” Vallejos said. “She said, ‘I don’t have the background to teach my kids. What am I going to do?’ She did everything right as a mom. It’s heartbreaking.”

Savanna Searles, who has two young children — a kindergartner and pre-kindergartner who attend Los Lunas Elementary School — said having the two of them working online at home has proven difficult.

The reason, Searles said, is because she is also going to school at The University of New Mexico-Valencia campus working towards a degree in secondary education, while her husband is at work all day.

“I don’t have the time to dedicate to what my kids need to learn,” Searles said. “I’m not managing very well. There’s a lot of things that my kids are missing in school, and I’m staying up until 3-4 a.m. trying to get my schoolwork done, and I’m just not waking up in time to put them in class at 9 a.m.”

Searles said she’s fortunate to be a stay-at-home mother, and feels for those parents that don’t have that same option because she knows it must be “twice as tough.”

Gonzalo Cano, twin brother of Gonzalo, an 11-year-old sixth-grader at Central Elementary School in Belen, works on an assignment during remote learning. He spends remote learning days at the Belen Community Center while his mother, Angela Cano, is at work.

Submitted photo

Anella Russo, who has four children — two of whom are in Los Lunas Schools and two she moved from the School of Dreams Academy to another charter school in Albuquerque — all have IEPs.

Russo has a 17-year-old junior with dyslexia and a 15-year-old sophomore who has ADHD — both attend Los Lunas High School. She said her junior, aside from having problems with reading, has problems with math as well.

But, she said, the district denied her extra help for the 17 year old despite getting a neuropsych evaluation that shows her deficiencies in math. For both children, she said, teachers seem more concerned with the camera being on during Zoom meetings and being signed-in.

Still, Russo believes remote learning is the best option in the midst of the pandemic.

Walter Gibson, LLS acting superintendent, said the district isn’t bringing kids back on campus with special needs, although he’s concerned for their progress in the remote model.

“We had the option from the governor and PED to bring special needs kids back on a 5:1 ratio, and some districts did that,” Gibson said. “Because we have so much better technology than most districts, we decided not to do that. That was a board decision. I agree with it. But I do worry that our most risky learners are missing the personal one-to-one contact with a teacher. If we thought we could do it safely, we would do it.”

Gibson said even with remote learning, students with IEPs are still meeting in much smaller classes, usually 10:1 or fewer.

Russo’s two younger children — a 12 year old with autism and a 10 year old who has a speech impediment — were both attending SODA at the beginning of the school year. But after not being provided Chromebooks by the school, her kids were marked absent for nearly an entire month.

When she asked for the devices, she said the school told her none were available. Eventually, SODA managed to get one device to the family, though that wasn’t adequate since she had two students.

Mike Ogas, superintendent of SODA, said when the pandemic hit in March, they “doled out” as many Chromebooks as they had. In June, the school ordered more than 100 more devices and another 150 in July. Those devices were supposed to be in by August, but now it has been pushed back to December.

Ogas said staff has been reaching out to parents, and most students have a device in hand. Those without a device have been getting paper packets. He added that SODA has seen an enrollment increase of 60-70 students.

“We are doing the best we can,” Ogas said. “We have worked very hard trying to get the devices we need.”

However, Jennifer Fritts said remote learning so far has been a positive experience minus a couple hiccups. She has two kids — a fifth-grader at Raymond Gabaldon Elementary School and an eighth-grader at Los Lunas Middle School — and both have been succeeding in classes.

Fritts said the IT department in the district has been helpful so far in making sure her kids are able to get their devices up and running.

Asked if she would keep her kids remote the rest of the school year, Fritts said “yes.”

“Mainly because my husband is sick and so any kind of virus like this could be catastrophic. But I would opt to keep my kids remote because if the tech issues are fixed, both of my kids do better,” Fritts said.