Music and dancing have been vital parts of Hispanic culture since Spanish colonial times in New Mexico. Filled with happiness, dancers enjoy a time and a place where everything in life seems aligned in perfect harmony. For a moment, all cares seem to vanish, replaced by joy and a sense of oneness with one’s dance partner, proud culture and Hispanic heritage.

New Mexicans enjoyed their music and dance in many venues, but perhaps most fondly in their dance halls of the 19th and 20th centuries. Nearly every village, city and town in New Mexico had at least one dance hall.

New Mexicans even enjoyed their dance hall in Barstow, Calif., where many families from the Rio Abajo had migrated, taking major parts of their culture with them in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s.

Who owned and operated these important enterprises? What made dance halls so popular for so long? Who attended their dances and which bands provided their music? What trouble occurred and what steps were taken to prevent disorder in or near dance halls? And what became of the dance halls that New Mexicans remember so fondly and miss so much?

Scattered in the Rio Abajo and beyond

It was almost impossible to visit a community in the Rio Abajo and not find a crowded dance hall filled with activity on Friday or Saturday nights. Most dance halls were simple adobe structures with sturdy tongue-and-groove hardwood floors and kerosene lamps in the days before electricity. Dance hall owners often scattered saw dust on their floors to facilitate dancers as they glided across the room.

Courtesy of Jim Sloan

Tabet Dance Hall, South Main Street, Belen.

Oldtimers recall that Tomé had two dance halls by its plaza, Adelino had one (owned by Miguel E. Baca), Los Chavez had one (owned by Frank Gabaldon), Jarales had one (owned by Joe Maestas), Los Trujillos had the Ortega Dance Hall, Abo had one, built beside its schoolhouse, and Belen had several, including Aragon Hall and its most famous, Tabet Hall, located on South Main Street and owned by Carlos Tabet Jr.

Sy Sisneros, who migrated to Barstow in 1950, built a 40-foot by 100-foot steel dance hall (when his original wooden building burned), calling it Abo Hall to help attract his former neighbors of the Rio Abajo who had joined him to live in California.

Dances were held almost every Friday and Saturday nights, except during Lent and other Catholic holidays. Special events, from showers and birthdays to weddings and anniversaries, were celebrated in dance halls. In 1938, a cowboy dance was held at Tabet Hall following a rodeo in Belen.

With a capacity of 500 dancers, Tabet Hall hosted countless benefit dances, including events to raise funds for St. Anthony’s orphanage (1952), the March of Dimes (1953), the Belen Police Department (1953 and 1954) and the Catholic Church in La Joya (1955).

The bands and their music

Dozens of popular bands played in New Mexico’s dance halls. Although some bands were small, many were large with as many as nine or 10 members.

Talented musicians sang and played one or more instruments. Nearly every band had musicians who could play accordions, guitars, violins, percussion instruments or trumpets.

Music and dances varied from the traditional to the more modern. Dance halls were filled with the lively sounds of polkas, rancheras, rumbas, mambos, boleros, country and swing.

John Collier photo, Library of Congress

The J.L.. Lopez three-man orchestra with local boys. Penasco, 1940.

Francisco Sisneros remembers his grandfather dancing traditional dances like La Varsovara, barrelitos, chotis and a dance that was much like musical chairs.

Bands knew dozens of songs. Most were about romance — won and lost. Others were about everything from personal tragedy to the misadventures of comical characters. Having heard these songs countless times, most dancers knew every melody, every lyric and every step that accompanied them.

Most dance hall bands were local, but some came from Albuquerque and, in one instance, from as far away as Corpus Christi, Texas. Some bands advertised an upcoming dance by parading through communities and playing a sample of the music they planned to perform at the dance hall. The bands traveled through the streets on carros de caballo (horse carts) in the early days and from the bed of pickup trucks in later years. Enticed by the sound of horns and guitars and violins, many villagers made plans to go to their dance halls and dance the night away.

Dance halls also advertised their events in local newspapers like the News-Bulletin. Some offered special door prizes to help attract customers.

In 1954, Tabet Hall offered a 26-piece silverware set, complete with a mahogany chest, to a lucky customer. Of course, you had to be present to win!

Dance hall customers admired the extraordinary talents and unique styles of many popular bands. Everyone liked and admired band leaders such as Isidero Amanda, Max Apodaca, Salo Chavez, Tony Chavez, Agapito Garcia, Don Lesmen, Tiny Morrie, Lalo Silva and Beta Villa.

Well-known bands were often family “businesses” that lasted one or more generations. Lalo Silva’s band, from Belen, included Lalo’s brothers, Prospero and Abran. Tony Chavez’s band, from Willard, included Tony’s brother, son and nephews. Agapito Garcia’s band featured Agapito’s sons, Sal and Isidro. The two sons later created their own bands, with Isidro’s band performing in Las Vegas, Nev.

Famous Albuquerque bands that played in Valencia County included Al Hurricane’s Night Rockers and Dick Bills’s Sandia Mountain Boys, which featured a handsome young singer named Glen Campbell. Jose Ruiz and his Happy Owls from Torrance County included a musician who did not let the loss of an arm in World War I prevent him from playing the trumpet — and being a one-armed pool shark.

The dancers

People came from near and far to frequent dance halls of the Rio Abajo. An article in the Rio Grande Express recalled that “local town folks, railroaders, ranchers, cowboys, Indians, and even city dudes from Albuquerque” came to join the fun at a time when there were few other forms of inexpensive entertainment.

Former Valencia County residents visiting from Barstow and the West Coast often came by to dance and meet old friends at the local dance halls, the social center of many communities each weekend evening.

J.E. Smith collection

Costume party, Socorro dance hall, about 1900.

Men and women of all ages danced, but a majority were youths, eager to socialize and perhaps meet new beaus or even future husbands or wives. Young women fixed their hair, applied their makeup and wore their prettiest dresses.

Young men made sure that their favorite clothes were washed and ironed, usually by their caring mothers and helpful sisters.

Lena Chavez’s brothers paid her a dime to shine their shoes, while their mother ironed their shirts with starch and pressed their dress pants with cleaning fluid to make sure their creases were crisp and sharp.

Neither sleet nor snow could keep the enthusiastic dancers away. Some youths went to great lengths to travel to dance halls, even when they lived at a distance and had other responsibilities to attend to at home.

Miguel E. Baca, for example, instructed his son, Carlos Baca, to camp out in their vineyard when Miguel noticed that thieves had begun stealing his grapes in Adelino. Carlos dutifully guarded his father’s five acres each night, but could not resist the temptation of accompanying his friends to a dance hall in Los Chavez on Saturday evenings.

Carlos and his friends rode horses across the Rio Grande with their good clothes tucked under their arms so they did not get wet in the crossing. Having crossed the river, the young men changed their clothes, enjoyed a night of dancing, and reversed the process when it came time to leave. Once home, Carlos returned to his post, guarding his father’s grapes like he had never left.

At the dance hall

Men and women traditionally occupied different parts of each dance hall. In the early years, young women, accompanied by chaperons, sat on bancos or tarimas (adobe or wooden benches along the side walls), visiting and patiently waiting for invitations to dance.

Meanwhile, most men sat across the hall, towards its back or outside where they talked, joked, smoked and drank liquor from small bottles to help summon the courage to ask eligible women to dance.

Males who had mustered sufficient courage ventured to where the women sat and asked their chosen partners to do them the honor of accompanying them in a dance. Early on, chaperons had to give their approval — or rejection.

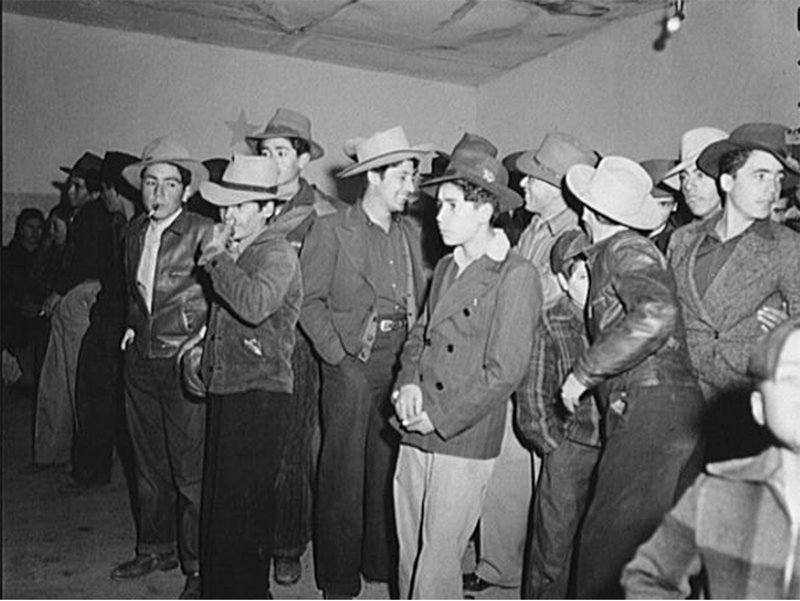

John Collier photo, Library of Congress

Working up the courage to ask for a dance. Penasco, 1940.

Later, women spoke for themselves, often accepting invitations, but sometimes turning men down for one reason or another. The smell of alcohol on a man’s breath might be enough to reject his advances, although he had ironically consumed the liquor to help build up the courage to ask a woman to dance. If rejected, a man experienced a “walk of shame” to rejoin his usually sympathetic friends across the room or outside.

Fortunately, there is no record of a scorned male resorting to violence after experiencing a woman’s rejection to dance in New Mexico. According to legend, such a tragedy occurred in Saltillo, Mexico. The beautiful Rosita Alvirez reportedly ignored her mother’s plea not to attend a dance alone and unchaperoned.

When an unsuitable man named Hipolito asked Rosita to dance, she refused his invitation. Humiliated before la gente (the people), Hipolito drew his pistol and shot Rosita three times. She died at the scene.

Rosita’s tragedy became so famous that it became the subject of one of the most frequently sung corridos (epic ballads) in Mexico and, eventually, New Mexico. It has been recorded over a hundred times, including by one of New Mexico’s most popular quartets, The Sparx.

But most women were pleased to be asked to dance and, with rare exceptions, happily accepted invitations by polite males. With lots of practice, some couples became famous for their dancing skills, winning dance contests and gaining the well-deserved admiration of their peers.

Beginning with a single dance, some relationships blossomed into friendships, romances and even engagements and marriages.

Becky Baca was visiting from California when she met her future husband, Salo Gabaldon, at Salo’s father’s dance hall in Los Chavez. Larry and Anna Rivera first met at Tabet Hall, as did Juan Contreras and Annie Lopez, who married in 1955, and celebrated their 50th anniversary in 2005. After five decades of marital bliss, Juan and Annie told a News-Bulletin reporter that they still enjoyed music and dancing together.

Co-author Matt Baca and his late wife, Theresa, went to a dance hall in Jarales on their first date. They were married for 58 years and danced every chance they could.

Misbehavior

Most dance hall events took place without incident. Unfortunately, this was not always the case, as with the tragic death of Rosita Alvirez.

Waiting outside, men often passed around bottles of whiskey, with predictable results as an evening wore on. Fueled by alcohol, verbal arguments or perceived insults easily led to fist fights, if not worse.

The smallest dispute could lead to gunplay or knifings. In 1925, a patron at a dance hall in Chimayo demanded that the orchestra play a third encore. When the musicians refused, the patron drew a revolver, pointed it at the band and declared, “You play or I will kill you.”

Dancers scattered. Several men and women were injured while trying to escape through a window. The disgruntled dancer proceeded to shoot a musician and a male bystander. The bystander died, leaving a widow and six children.

In 1951, the Belen News reported that as many as 15 men engaged in a “major disturbance” at Tabet Hall. Two men suffered head injuries. Four men from Albuquerque faced charges before the local justice of the peace.

Local rivalries and romantic jealousies could also lead to violence. Young males were especially jealous of out-of-town rivals who vied for the attention of local beauties.

John Collier photo, Library of Congress

Ladies in waiting at a dance hall in Penasco, 1940.

When Carlos Baca and his friends from Adelino crossed the Rio Grande, the young men of Los Chavez dismissively called them hongos (mushrooms, because mushrooms were prevalent in Adelino) and challenged them to fights over especially attractive girls.

Carlos occasionally returned home with a black eye, the result of such a fisticuff. Carlos tried his best to conceal his injury at Sunday morning breakfast so that his father would not see the blatant evidence that proved Carlos had not only abandoned his guard post in the vineyard, but had also gotten into a fight — and lost.

Years later, when he had married and had children of his own, Carlos, his wife, Felicitas, and their three children were about to go to a dance hall (actually a gym behind the nearby Adelino school) when a neighbor came to their door, weeping that her husband had gotten drunk and had threatened to harm her and their kids. Carlos allowed the woman and her children to take refuge in his home as he and his family went off to the dance.

Carlos and his family were not at the dance for long when the woman’s intoxicated husband arrived, searching for his wife by riding his horse into the hall, shooting his pistol in the air and yelling as he entered. The guests fled at the sight of their inebriated neighbor atop a huge horse in the middle of the dance hall’s floor.

An even more violent event occurred in Los Trujillos in December 1951. Home for the holidays, 20-year-old Pvt. Felipe Sanchez had enjoyed an evening of dancing at the Ortega Dance Hall when he was attacked by a 16-year-old stranger from Albuquerque.

The stranger stabbed Sanchez seven times. Witnessing the assault, a deputy sheriff chased the teenager for about 50 yards and shot him in his side. Fortunately, Sanchez and his attacker both survived.

Dance hall owners did their best to keep the peace in their establishments. Violence was so prevalent at a dance hall in Vado during the 1930s that the hall’s owner placed a sign over the entrance that read, “Check your hats and weapons at the door.”

Sy Sisneros routinely hired two off-duty sheriff deputies to maintain order during dances at his Abo Dance Hall in Barstow. He hired an extra deputy for wedding receptions. In greeting the deputies, Sy pointed out known potential troublemakers before each night began.

Carlos Tabet hired Jim Barnes, a moonlighting railroader who was so big that it was said that he maintained order at Tabet Hall by his intimidating size alone. Unfortunately, rowdy customers who were bounced out of Tabet Hall often walked down the road in search of additional trouble at other dance halls on Main Street in Belen.

Dance halls’ fate

Dance halls remained popular into the 1960s, but modern developments and man-made disasters often spelled their doom.

In Adelino, a careless driver on N.M. 47 crashed into the east wall of the Bacas’ long adobe dance hall. The remaining structure became so unstable that Carlos eventually leveled the building.

Proximity to highways sealed the fate of at least two other dance halls. In Belen, Tabet Hall was impaired when the state widened South Main Street to make it into a four-lane road in the mid-1960s. The last dance at Tabet Hall was held in March 1964. Fires, including one that police suspected to be arson, caused great damage in 1968 and on July 4, 1972.

John Collier photo, Library of Congress

Penasco dance hall, 1940.

In Barstow, Sy Sisneros’s Abo Hall fell victim to the opening of a new highway south of town. Originally on the main route between Phoenix and Las Vegas, Sy’s dance hall and other local businesses suffered badly and eventually closed. Sy sold his large hall for $12,000. It has since been converted into a garage used for semi-truck repairs.

Dance halls also faced modern competition in entertainment. A hall in Los Chavez was converted into a skating rink. By the 1970s, dance halls were largely replaced by modern commercial lounges and night clubs like the Red Carpet and the Wild Pony in Valencia County, and the Caravan East and West along Central Avenue in Albuquerque.

Deejays often replaced real bands. Offering liquor and other amenities, night clubs provided entertainment nearly every night of the year.

Popular music changed as well. Rather than listening and dancing to Spanish music, a new generation of the 1950s and 1960s listened to rock ‘n roll, dancing with gyrations that bore no resemblance to traditional Spanish steps and moves.

And so the dance halls of the Rio Abajo — and most of New Mexico — are gone, mourned by the thousands who nostalgically recall the good times they enjoyed there. A large part of New Mexico culture has disappeared with the dance halls’ demise.

But all is not lost. Spanish music is still played by popular bands and on favorite radio stations. Couples still dance, especially at fiestas, weddings and other special events.

And, as one former dance hall patron has said, we can still visit the sites where the halls once stood. If all is quiet and “if one listens closely you can still hear the music and the dancing feet of yesteryear.”

The dance halls are gone, but the memory of their magic lingers in our collective musical minds.

(La Historia del Rio Abajo is a regular column about Valencia County history written by members of the Valencia County Historical Society since 1998.

Although co-author Richard Melzer has two left feet, his parents met at a dance studio and became champion ballroom dancers. Co-author Matt Baca’s grandfather, Miguel E. Baca, owned a dance hall in Adelino. Matt’s father, Carlos Baca, plays a prominent role in the following story. Matt and his late wife, Theresa, were often called on to lead La Marcha at traditional New Mexico weddings.

Opinions expressed in this and all columns of La Historia del Rio Abajo are the authors’ alone and not necessarily those of the Valencia County Historical Society or any other group or individual.)

(Readers interested in joining the Valencia County Historical Society can contact its president, Richard Melzer, at [email protected].)