(Editor’s note: The below article has been corrected to indicate the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District’s proper role in the sale and transfer of pre-1907 water rights, as well as a property owner’s right to have a domestic well and be connected to a domestic water system.)

LOS CHAVEZ — Water.

In New Mexico and throughout the desert southwest, it is a precious, scarce resource. How it should be used, managed and doled out are topics of hot debate, and across the globe, communities struggle to keep up with water demand for direct human consumption, commercial and agricultural uses.

“We are in a new normal of water availability. We’re going to have to accept we’re have a different climate than what we had in the 1980s,” said Stephanie Russo Baca, staff attorney and ombudsman for the University of New Mexico School of Law’s Utton Center.

She is also the chairwoman of the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District board of directors.

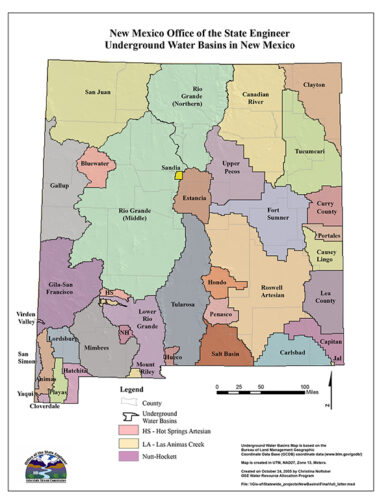

Courtesy of the New Mexico Office of the State Engineer

New Mexico has 39 declared groundwater basins. Any water rights transfers must stay within the originating basin.

Julia M. Dendinger | News-Bulletin photo

Working from her Los Chavez home, water attorney and ombudsman for the Utton Center Stephanie Russo Baca explains the complex water laws that dictate proper use of the precious resource across the state.

According to the most recent information released earlier this month by the U.S. Drought Monitor, the vast majority of the state is in some kind of drought condition. Most of Valencia County is in a severe drought condition, with the far eastern edge in moderate drought conditions.

A year ago, 12.94 percent of the state was classified as having no drought conditions. As of Aug. 16, that has shrunk to .60 percent. The number of areas in exceptional drought has also shrunk, from 1.68 percent in 2021 to .33 this year. Going back to June of this year, however, 46.76 percent of the state was classified as being in an exceptional drought, including Valencia County.

Areas in the conditions between the two extremes have mostly increased — both abnormally dry and moderate drought areas have increased by just more than 12 percent, and extreme drought conditions have increased by nearly 5 percent. Severe drought areas have decreased by .49 percent.

The U.S. Drought Monitor — droughtmonitor.unl.edu — is produced through a partnership between the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the United States Department of Agriculture and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“No use is any more or less important than the other. Is a bottling company more of a burden than agriculture? For the state engineer, it does not matter,” she said. “Maybe that’s something in New Mexico that needs to change. But your team might not be the winner.”

While hydrologically connected, in New Mexico groundwater and surface water are statutorily two different things. The New Mexico Office of the State Engineer has authority over both groundwater and surface water.

“Groundwater is just what it sounds like. It comes from underground from various groundwater basins,” Russo Baca said.

Valencia County sits on the Middle Rio Grande basin, which runs from the southwest corner of Rio Arriba County, through Sandoval, Bernalillo, Cibola, Valencia, Catron, Socorro and Sierra counties. There are 39 declared groundwater basins in New Mexico.

“Surface water comes from the surface — our rivers, our streams — and they both have a beneficial use,” she said.

Typically, groundwater is used for household, commercial and industrial purposes, while surface water is used mostly for crop irrigation in Valencia County.

“You’re not going to divert surface water to put into a tank that you then use for your house,” Russo Baca said.

Domestic wells are permitted one acre foot of water use annually, but the property has to be less than an acre. An acre foot is the amount of water needed to cover an acre of land in a foot of water — 325,851 gallons.

“So if you wanted to use that in a sprinkler system or drip irrigation in a garden, you can make one acre foot go a long way.”

Source: Upper Rio Grande Water Operations Model

When a well is permitted by OSE, an applicant has to declare a use, Russo Baca said, for example either domestic, livestock or commercial, which includes agriculture.

“Say you buy an acre of property and there’s no well on it. You can apply for a permit for the well,” Russo Baca said.

However, some jurisdictions have prohibited the use of a domestic well on a property in conjunction with a connection to a domestic water system. Since August 15, 2006, the OSE adopted new regulations governing domestic wells, however, these regulations did not affect existing domestic wells, livestock or temporary wells. They only affect new domestic wells.

Under the new regulations, domestic use of water is limited to one acre foot per year per household. Further limitations to the amount diverted may be imposed, by the courts, by municipal or county ordinances, or by the State Engineer.

Whether the water is on the surface or under the ground, people have a right to use it, but it’s not necessarily owned by the user.

“You have a right to use the water. It’s kind of like leasing a car. It’s not really yours. You can use the car but then you eventually have to give it back to the dealership,” Russo Baca said. “In a way, the dealership is the whole state of New Mexico.”

Anyone with questions about water rights should reach out to the OSE, she advised.

“They are very helpful and willing to help find information.”

Transferring water rights, changing the point of diversion and place of use of the water is all done through OSE, whether they are surface or ground water rights. While these transfers result in what are colloquially called “paper” water rights — the physical water isn’t moved from one location to another — all those rights have to stay within the same basin.

In addition to the OSE requirement that water transfers remain within the same basin, the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District has its own policy which obligates it to protest junior or post 1907 water rights transfers out of the MRGCD’s benefited area.

Only water rights with a pre-1923 priority can be transferred without the consent of the MRGCD. Consent from the district is required when anyone proposes to transfer water rights with a priority date of 1923 or later. This is because MRGCD claims title to all unclaimed surface water in the basin as of the time its works were first constructed in 1923.

“The MRGCD’s job is to deliver water for irrigation. If all water rights are transferred out of the district, there’s no water to deliver,” she said.

Russo Baca represents Valencia County on the district’s board of directors.

“As board members, we sign an oath to protect the district,” she said. “If all the water rights were transferred out, then that would not be protecting the district.”

Another fierce battle centers on what is the best way to use water. In New Mexico, the law doesn’t recognize a hierarchy of uses, Russo Baca said. In the eyes of the law and OSE, domestic use, commercial and agricultural uses are all equal.

Julia M. Dendinger began working at the VCNB in 2006. She covers Valencia County government, Belen Consolidated Schools and the village of Bosque Farms. She is a member of the Society of Professional Journalists Rio Grande chapter’s board of directors.