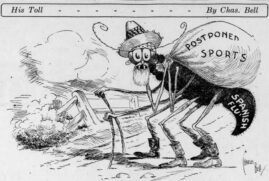

The last edition of La Historia documented that many Americans reacted to the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 by wearing masks. Most people wore masks voluntarily, knowing that masks were their best front-line defense against spreading or catching the fatal flu.

In cities like Taos, Tucson and Oakland, residents were required to wear masks or face arrest, with fines or jail time to follow. Few Americans objected because they were determined to defeat the flu with the same strong will they had displayed in helping the United States soundly defeat Germany and its allies in World War I.

Keeping a healthy sense of humor

Most Americans faced the need to wear masks with the help of appropriate, good-natured humor. One observer, for example, suggested people who wore masks now had more sympathy “every time they encountered a horse wearing blinders and grinding his teeth on an iron bit.”

Another wit believed that wearing masks was “a God-send in one respect” because masks “made it possible to talk to some people whose breaths have needed a muzzle for a long time.”

A comic in Ohio suggested that “the only way to make some fellows wear a flu mask is to sprinkle a little whiskey on it.”

At least one reporter saw a silver lining to the wearing of flu masks because it might well reduce the use of cigars, cigarettes and tobacco. Of course, some people wanted the best of all worlds. B.D. Greene, an attorney in Berkeley, “attempted to enjoy a nice, comfortable smoke in his office … with his influenza mask properly adjusted on his face.”

Shouts of “Help, fire!” came from Greene’s office. People rushed to his aid, only to find him “hopping about the floor and attempting to tear a burning influenza mask from his face.”

“I was only trying to live up to the new mask law,” Greene explained when the fire was extinguished and the excitement had subsided. The press noted that Greene’s injury was “slight, but his mask was a total loss.”

The manager of a West Coast amusement park and his five monkeys were not as fortunate. Believing Darwin and his theory of evolution, the manager thought it would be prudent to protect his vulnerable animals from the flu.

The press reported that the monkeys strenuously objected to wearing the masks and spent several days trying to remove them. Once successful in pulling off their masks, the monkeys “promptly ate them, with fatal results.” The story ended with the sad news that “the flu did not kill them, but the flu masks sure did.”

On the brighter side, in a joke that must have appeared in half the newspapers in the country, a boy told his mother, “Isn’t it nice, mother, that Daddy has such big ears,” to anchor his mask!

The Tampa Times ridiculed a “prominent and portly” minister who took some strange extra precautions when he visited sick members of his church. The pastor wore a gas mask on his face and a towel wrapped around “his generous middle distance.”

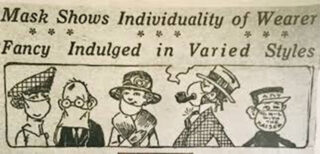

It was not long before newspaper cartoons began to find humor in wearing masks. Reporters also kidded about people not being able to recognize their own friends when they wore masks.

Challenging readers to identify her, an Indiana newspaper printed the photo of an attractive young woman in a mask. Many couldn’t recognize the most famous movie star of that era: Mary Pickford. Sports fans in Tampa were also asked to identify well-known baseball players pictured wearing masks.

Crime

Flu masks created an unexpected challenge in maintaining law and order. While hardly causing a crime wave, individual cases of theft appeared in newspapers on a rather regular basis.

In Buffalo, for example, two men wearing masks held up a woman storekeeper as she was closing her shop. The pair stole $60 in cash, a $50 Liberty Bond and an overcoat.

A tailor from Berkeley reported that a bandit held him up, taking $1,000 in War Saving Stamps, $1,000 in Liberty Bonds, $20 in cash and a $10 watch for a total of $2,030 in loot, equal to $41,000 today.

In an ironic tale, a doctor’s chauffeur had driven the physician to make a house visit and was waiting outside when two masked men approached. One thief pressed a gun to the chauffeur’s ribs and told him to keep still while he took the man’s wallet with $38 inside.

Meanwhile, the second thief started the car and, when his partner jumped in, sped away. The chauffeur tried to follow on foot, but lost sight of the automobile when it turned and merged into city traffic.

Robbers wearing flu masks also broke into homes. In one instance, a so-called “polite burglar” entered a woman’s bedroom through an open window. When the woman awoke, the masked intruder told her to simply tell him where she kept her money. The frightened woman indicated a bureau where the robber found $7 and a camera. Disappointed, the man demanded to see the woman’s hands, taking an engagement ring valued at $140.

As he exited out the same window he had entered through, the “polite” crook turned back and said, “In the future I would advise you to keep your window locked when you go to bed.”

With so many people wearing flu masks there were bound to be cases of mistaken identity. In one case, a masked man climbed a ladder to hang political banners on a wall during the 1918 election campaign. Seeing the suspicious looking man, a police officer apprehended him and brought him to the police station.

The arrested man explained what he was doing and convinced the desk sergeant that he was not a criminal, despite his face mask and ladder. The press reported that the sergeant saw the humor in the incident, “laughed heartily” and sent the suspect on his way.

Opposition

While most Americans cooperated with flu mask ordinances, certain factions did not. Some were more insistent and vocal than others, doing everything from writing letters to editors to making threats against health officials. One such health official in San Francisco received a bomb in a box addressed to him. Fortunately, it did not explode.

A faction objected because “pesky shrouds” interfered with their use of tobacco. One disgruntled 75-year-old man was so upset by his arrest that he armed himself with a handful of mothballs and threw them into the courtroom when his case was heard.

E. Piercy declared that “of all the fool laws ever passed this … darned flu mask ordinance is the limit … I claim that tobacco will kill flu germs with a greater degree of efficiency than any blamed flu mask ever invented … I’m not going to give up my tobacco for a cheesecloth muzzle!”

A Minnesota banker announced that he planned to move to Southern California because he “must have my smoke — and I just dearly love to smoke at times while on the streets.”

After paying his fine for not wearing a mask in Pasadena, the culprit declared that it was “back to Los Angeles for me, where I can get a little fresh air and where cigars look better in a man’s mouth than flu masks on a man’s ears.”

An observer reported that two “cowpunchers” in Tucson entered a cigar store “with their masks hanging under their chins.” The same observer noted that the cowboys and all others who chose to “rock the boat” regarding masks were more “distinguishable by their muscular development … than by an intelligent brow.”

Another faction objected to wearing masks because they believed that the garments interfered with their ability to work safely and efficiently. In Atlanta, nearly every employee of the A.B. & A. Railroad walked off their jobs, refusing to return until the local ordinance requiring masks was repealed. In Buffalo, the police wore masks but insisted on cutting holes in them so they could breathe more easily when chasing crooks.

A West Coast truck driver refused to wear a mask after his mask caught on fire while he repaired his truck. The worker suffered “serious wounds,” including the loss of his eyebrows and hair and injuries to his eyes and nose. A doctor dressed his wounds, but the driver still refused to don another mask.

A third group of objectors refused to wear masks based on their strong belief that masks were unsanitary and, therefore, unsafe. In early Nov. 1918, 35 residents of Berkeley filed a petition to their city council, demanding that the mask ordinance be repealed because they considered masks to be unsanitary. The city’s public health department refused to change its policy regarding masks, insisting that “it would be foolish to relax precautions now just as the malady shows signs of being checked.”

A month later, a group of concerned citizens in San Francisco organized one of the nation’s only Anti-Mask Leagues. Meeting at the Dreamland skating rink, league leaders declared that masks were “insanitary and useless.” The organization raised $100 to help fight the board of health’s enforcement of the reviled ordinance.

A poet in Louisiana did not join the league, but used his literary skills to “dash off” a poem in protest. “My Flu Mask” concluded that “A flu mask is a germ-retaining thing!” Meanwhile, a popular magazine, the Literary Digest, ran an article titled, “How the Flu Mask Traps the Germ.”

Other critics expressed doubt that masks could prevent flu germs from spreading into mouths and nostrils. One detractor claimed that using masks to prevent the spread of flu germs was “like using barbed-wire fences to shut out flies.” Another cynic said that using masks to prevent the flu was like trying to keep criminals in a jail cell with 5-feet between its iron bars.

Of course, masks could not be effective when they were not made or worn correctly. A man in Wyoming made his from a thin “cheese cloth with common twine for strings.” A good many people wore their masks over their mouths, but not their noses. The average male in Utah reportedly wore his mask slung to the back of his neck until he saw a policeman walking in his direction.

A Tucson attorney was said to have made his case against masks while he drank a “commonly imbibed beverage,” followed by glass after glass of water as chasers. Drinking so much liquid gave the lawyer a good excuse to “let his mask dangle.”

Between gulps of water and booze, the lawyer argued against the use of masks, declaring that it was “in reality a menace to the health rather than a preventive of disease.” No one mentioned that the lawyer’s “commonly imbibed beverage” was also a menace to one’s health in the long run.

Lessons learned

Much of what Americans experienced when wearing masks during the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 sounds familiar to us today. But we are fortunate that much is also different, especially in terms of local ordinances and arrests.

While some Americans protested against these rules and arrests in 1918, not even the insistent Tucson lawyer objected to them as an infringement of his constitutional rights and civil liberties, as we often hear today. Americans of the post-war period debated other major constitutional issues, from prohibition to the teaching of evolution, but they seldom considered measures taken for public health to be one of them. Few Americans made wearing a mask or not wearing a mask a political issue during the election year of 1918.

The United States had just won the First World War, largely as a result of its citizens making needed sacrifices, from conserving food to sending loved ones into battle. Asking people to endure wearing masks to fight a new, more deadly enemy seemed like an extension of the war when soldiers on the front lines knew the wisdom of wearing gas masks, no matter how uncomfortable they might be.

Americans were therefore ready and willing to sacrifice for the greater good. As the Arizona Daily Star editorialized, “the enforcement of any law is accomplished by popular support rather than by the summary use of the police power.”

And there was proof that masks were effective in 1918, with statistics showing that communities that required the wearing of masks reported far fewer cases of the flu than those that did not.

Perhaps the greatest proof of the effectiveness of wearing masks came when a U.S. Navy transport carried 6,000 American soldiers to a British port near the end of the war and at the height of the epidemic in late Oct. 1918.

While the flu ran rampant in stateside camps like Camp Cody in southern New Mexico, only 50 cases of the disease and one death occurred on the transport. The press reported, “The success achieved in combating the malady was due, in the opinion of physicians, to the fact that every man wore a cloth mask during the voyage.”

In comparison, the 4,850 soldiers on another transport, the USS George Washington, were not required to wear masks on their journey to France. More than 500 caught the flu and 77 men died of the disease.

And so the lesson to be learned from our forefathers in 1918 is that, despite their inconveniences, masks are effective in preventing the spread of airborne viruses, such as COVID-19 and the flu.

Please remember that no matter how physically difficult and uncomfortable it is to wear a mask, it is far more difficult to experience the death of one or more loved ones during this, the worst health crisis of our lifetimes.

(Those interested in joining the Valencia County Historical Society should contact its president, Richard Melzer, at [email protected].)

(La Historia del Rio Abajo is a regular column about Valencia County history written by members of the Valencia County Historical Society since 1998.

The author wishes to thank Dr. Richard Madden for kindly lending his medical expertise in the writing of this column.

Opinions expressed in this and all columns of La Historia del Rio Abajo are the author’s alone and not necessarily those of the Valencia County Historical Society or any other group or individual.)

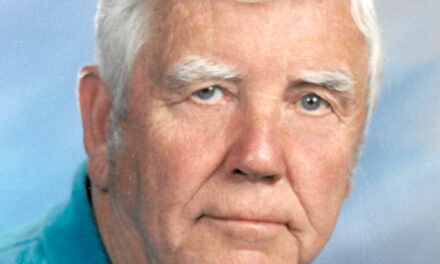

Richard Melzer, guest columnist

Richard Melzer, Ph.D., is a retired history professor who taught at The University of New Mexico–Valencia campus for more than 35 years. He has served on the board of directors of the Valencia County Historical Society for 30 years; he has served as the society’s president several times.

He has written many books and articles about New Mexico history, including many works on Valencia County, his favorite topic. His newest book, a biography of Casey Luna, was published in the spring of 2021.

Those interested in joining the Valencia County Historical Society should contact Dr. Melzer at [email protected].