After weeks of sheltering in place, many of us long for the day when we will be able to socialize and move freely whenever and wherever we please. By now, we all know the name for what we suffer: cabin fever.

No one would disagree that we are living through difficult times, but it could be far worse. It was not too long ago that the threat of an epidemic caused communities to isolate the infected in small dwellings known as pestilence houses, or pest houses for short. Some residents also called these structures pest houses because they considered their infirmed inhabitants downright pests and a menace to society.

Patients in pest houses usually received as much care as possible, while accomplishing the main goal of preventing the spread of highly-contagious diseases to the rest of a community’s vulnerable population.

Pest houses have existed in all parts of the world for centuries. In New Mexico, they date back to the mid 19th century, usually to help combat smallpox, New Mexico’s deadliest, most frequent affliction.

Who?

With few hospitals in New Mexico until after 1900, pest houses could be considered temporary isolation wards, especially for the poor who lacked access to regular medical attention, no less urgent care.

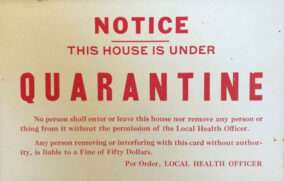

In contrast, middle- and upper-class patients with contagious diseases usually stayed at home, where they could receive medical care in home visits by doctors and nurses. These more fortunate victims of disease were simply required to warn the public by placing “quarantine” signs on the exterior of their homes.

City ordinances often required that residents report suspected individuals so that the police could apprehend them and escort them peaceably or forcibly to the local pest house. In 1882, a Las Vegas city ordinance required the police to “proceed at once to the place … where the person or persons suffering with said disease are lodged, and shall demand at once the removal of said person … to the pest house.”

Anyone who knew of an infected neighbor was required to inform the police so they could arrange “for their immediate removal to the pest house.”

An English pest house of the 19th century.

Pest house occupants came from every conceivable background and occupation. Transients were quickly sent to pest houses if they showed any sign of being a danger to a community after arriving with a contagious disease. In 1898, for example, the press reported that “a wandering outcast of the genius tramp” had arrived in Albuquerque. Afflicted with smallpox, the homeless man “was intercepted” and quickly dispatched to the pest house.

In the terrible winter of 1881-82 miners at the new town of Kingston had little shelter for the healthy, no less those afflicted with smallpox. The town’s only doctor was said to be a “hard drinker” who, when “loaded,” readily pulled off his hat and wig to expose where he had previously been scalped by Indians.

When sober, the doctor ordered that the largest tent in town be made into a pest house. Two “grog heads” were hired as “nurses,” although they insisted on being paid with a jug of whiskey each day. Local women furnished meals, but the so-called nurses ate most of the food and were soon fired.

As “ladies of the night” were known to do in similar emergencies, three “soiled doves” traded their fine dresses for plain attire and volunteered to work as nurses at the Kingston pest house until the crisis had passed. The novice nurses soon had the disease under control.

At least one profession made arrangements for the opening of a pest house to treat its members. In 1883, a printer named “Dutch” Snell collapsed on the sidewalk in front of the Albuquerque Democrat’s newspaper office where he worked. Snell died a few days later, a victim of smallpox.

Alarmed, other printers in Albuquerque rented an old adobe house and arranged for a doctor to run it as a pest house for printers only. Fortunately, the six printers who caught smallpox and took shelter at the pest house survived, including a printer with an unforgettable name: George Washington.

Another George, George Atkinson, had recently arrived in Albuquerque from Colorado when he landed a job as a bartender at the Home Ranch Saloon. He had just started work in April 1903 when he caught smallpox and was sent to the pest house some distance east of town. The press did not report if the Home Ranch Saloon offered him a case of liquor to pass the time in isolation.

What and where?

The construction and size of pest houses varied from one town and epidemic to the next. Some structures were made of adobe with dirt floors, few amenities and poor air ventilation. Most pest houses were small, with no more than a few rooms. Other than the county physicians who came by, health care professionals were scarce. Attendants were seldom well trained, no less adequately paid.

Although some pest houses were slightly larger and more sanitary, they seldom met the minimum standards of a true hospital. Most people considered being taken to a pest house to be little more than a death sentence. Pest houses were identified as places to die more often than places to recover and renew life.

In fact, pest houses were often located on the edge of towns not far from local cemeteries, where patients who died could be buried, often at public expense, as happened to a pauper in Santa Fe in 1884. Albuquerque’s town leaders placed a pest house in the sand hills south of the city’s few cemeteries during the smallpox epidemic of 1881.

Of course, the main reason for having pest houses on the edge of town was to keep their sick inhabitants as far from the general population as possible. At various times, Albuquerque had one or more pest houses, including in the undeveloped northeast, on the east mesa and to the far south.

In 1891, Gallup residents considered placing their pest house near an old mine. In 1915, the Grant County physician suggested the use of an old house near the slaughter pen in Lordsburg. Equally distant locations were identified outside towns and cities such as Albuquerque, Gallup, Raton, Silver City, Socorro and Tucumcari.

Troubles abound

In addition to poor medical facilities and care, pest houses often suffered a long list of serious problems. Some were considered excessively expensive.

In Santa Fe, civic leaders calculated that running the pest house during the smallpox epidemic of 1883 had cost a total of $315.70, including $154.40 for food, $83.20 for furniture, quilts and blankets, $11.65 for firewood and $30 for rent. About half of these expenses were covered by private citizens, although some citizens never paid their promised contributions.

In 1902, residents of Socorro remembered the problems they encountered during their last smallpox epidemic. The Socorro Chieftain reported there had been no money in the general fund “owing to tax resisters, tax dodgers, and tax eaters.” As a result, the mayor had “to go around begging from citizens to procure funds to establish a pest house,” feed the patients and burn their clothing whether or not they survived.

A quarantine sign hung on the homes of patients with communicable diseases.

Dr. Charles F. Blackington had treated the patients gratis and had even advanced them money out of his own pocket “for the road.”

Expenses could run higher if patients made even moderate requests. A railroad worker named Will M. Robertson was confined to the pest house in Alamogordo in 1903 when he contracted measles. After a few days in isolation, Robertson sent out a note that read: “Please send me some beef steak, one can of syrup, some rice and a towel. Send also some whiskey and see if you can scare up an old deck of cards.”

Pest houses were also vulnerable to mishaps when they were largely neglected between epidemics. In late 1912, Albuquerque’s abandoned pest house, located a quarter of a mile outside the city limits, caught fire when one or more persons shot holes in the structure’s shutters and window panes. One of the shooters apparently threw a lighted match through one of the bullet holes he had made. The match had landed on a bed, causing the fire to start. Fortunately, the damage was neither excessive nor deadly because the building was made of concrete blocks and there had not been a patient in the house for nearly two months.

Four years later, a fire “of incendiary origin” destroyed most of what remained of the same pest house. Firemen responded to the alarm but were unable to reach the remote building with adequate water. The flames were so high that residents could see them from many parts of the city.

Thieves also exploited abandoned pest houses. In 1920, the Albuquerque health department discovered a pest house had been broken into and robbed in the city’s southwest. Thieves had removed two beds, a small stove and pieces of bedding. Not even a large Yale padlock and new sheet iron doors and shutters had deterred the burglars. The Albuquerque Journal suggested it might be necessary to post a guard to deter future crimes of this kind.

Not all doctors or attendants could be trusted. The town marshal in Las Vegas investigated two doctors for “dishonest transactions” in 1882. Perhaps feeling they had not been adequately compensated for their labors, one doctor was accused of taking $50 from a patient, while the other doctor reportedly took off with a watch, a chain and other valuable personal property.

A most “sensational” scandal

Women reporters like Nellie Bly, of New York City, often became famous for infiltrating prisons, mental hospitals and other public institutions to expose the serious problems they found there. No newspaper men or women attempted this sort of investigative reporting in New Mexico’s pest houses, but one woman entered a pest house and wrote a sensational letter to the city council equal to any Nellie Bly exposé of the time.

When Mary D.E. Wilson contracted smallpox in early 1908, she was confined in an Albuquerque pest house for several weeks. Her husband had opposed her confinement, but was assured that the pest house had separate facilities for women, and that Mary’s mother could accompany her to help in her recovery.

But nothing was as promised. The facility for women was so squalid that Mary and her mother had to sleep in a room with a male patient and a “Mexican” attendant. Except for a few planks, the floor was dirt. Old cots “of the cheapest kind” were reinforced with baling wire. The roof leaked and suffocating dirt blew through cracks in the walls.

Mary wrote of a dirty kitchen table, fresh meat left out in the open and undisposed trash. Water was kept in whiskey barrels and “tasted so strongly of whiskey that it was sickening.” Mary did her own cooking and cleaning, especially after her mother had to return home and the otherwise helpful attendant left.

Mary concluded her letter by asserting that no one should be “imprisoned” in such a place and “be treated worse than convicted felons.” She insisted that the city council and board of health take her charges seriously and begin to implement needed reforms.

The city defended itself with letters by the county physician, Dr. C.H. Carns, and by several more satisfied former occupants of the pest house. Albuquerque’s two major newspapers, the Journal and the Citizen, gave Mary’s story front-page coverage, and the Citizen wrote a lengthy editorial. But news of the pest house faded quickly and it is likely that only cosmetic changes were made for lack of funds or sustained interest.

Great escapes

Pest houses were meant to not only cure the ill, but also protect the healthy. This was only possible if patients remained in confinement, avoiding the temptation to take a short trip into town or escape these dismal conditions completely.

In 1882, for instance, the press in Las Vegas reported seeing several patients from the pest house circulating about town freely. One pest house occupant was observed spending much of his day lounging in the post office and other public places.

“There is no excuse whatever for their criminal action,” wrote the Las Vegas Optic. “Such persons should be warned of the crime they are committing and then if they do not desist a committee should wait upon them.”

Committees that “waited upon” trouble makers in Las Vegas in 1882 usually carried a noose to impress the accused that they meant business.

In 1898, a “colored” patient at an Albuquerque pest house decided to take a walk one Sunday, telling the guard that he had the marshal’s approval. Instead, the patient headed down the railroad track and got lost in a storm. A deputy searched on horseback until he finally found the man three miles out of town.

The Albuquerque Citizen reported that the deputy brought the escapee back “at the point of a revolver.” The pest house guard was thereafter given a gun and told to use it in case the patient insisted on taking another stroll without actual consent.

Pest House Medical Museum, Lynchburg, Va.

The youngest person to escape from a pest house never actually lived in one. In 1919, an Albuquerque city worker named George W. Straw made plans to take his 5-year-old son to Belen on a bicycle. Straw strapped a suitcase to the back of his bike and placed a small seat for his son on the handlebars.

When a city health inspector received word that the boy had smallpox, he attempted to prevent the trip, pointing out to the father that the boy might spread the disease in the communities they traveled through in route to Belen. Straw replied that he planned to go through settlements so fast that local residents would not see the boy, no less catch smallpox from him.

When the health inspector returned with a car to transport the boy to the pest house, the young fellow and his father were long gone. Having lost his wife to the Spanish flu the previous year, Straw did not want to lose his son to an uncertain fate in the pest house.

Closing down

Mercifully, pest houses had become a thing of the past by World War II when smallpox and other major diseases had been largely eradicated. Abandoned pest houses became play houses for many kids who roamed the mesa east of Albuquerque in the 1940s and 1950s. Albuquerque suburban developers destroyed the last pest houses in what became the Northeast and Southeast Heights. General hospitals such as Presbyterian in Albuquerque and St. Vincent’s in Santa Fe offered modern isolation wards and intensive care units far superior to any services offered in primitive pest houses.

Only a few old-timers remember what pest houses were, no less where they were located and what role they played in the United States, including New Mexico. For those who care to revisit this largely forgotten part of history, there are scattered references in old newspapers and even a small Pest House Medical Museum in Lynchburg, Va.

Pest houses served a vital purpose. But they were like small dams, barely able to contain small floods, no less tsunamis like smallpox epidemics, the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 and tuberculosis.

Although largely crude and inefficient, pest houses were the best that most communities could manage and afford. It was a small vision but, as Solomon once warned in the Bible, “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” (Proverbs 29:18, KJV)

(La Historia del Rio Abajo is a regular column about Valencia County history written by members of the Valencia County Historical Society since 1998.

Opinions expressed in this and all columns of La Historia del Rio Abajo are the author’s alone and not necessarily those of the Valencia County Historical Society or any other group or individual.)

Richard Melzer, guest columnist

Richard Melzer, Ph.D., is a retired history professor who taught at The University of New Mexico–Valencia campus for more than 35 years. He has served on the board of directors of the Valencia County Historical Society for 30 years; he has served as the society’s president several times.

He has written many books and articles about New Mexico history, including many works on Valencia County, his favorite topic. His newest book, a biography of Casey Luna, was published in the spring of 2021.

Those interested in joining the Valencia County Historical Society should contact Dr. Melzer at [email protected].