Ben Franklin famously declared that only two things in life are certain: death and taxes. Old Ben was right, but he forgot one other certainty, which we experience every 10 years: the U.S. census.

It’s curious that Ben forgot to include the census because it’s required in the U.S. Constitution that he helped write in 1787. Of course he never experienced a census because he died about four months before the first census was taken in August 1790.

The main reason we have a census is to calculate how many representatives each state can elect to the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. New Mexico had only one representative from statehood in 1912 until we gained a second representative in the 1940s and a third in the 1980s when our population grew to 1.3 million.

As we experience another census this year, it is interesting — and sometimes amusing — to consider the history of previous censuses in New Mexico under Spanish, Mexican and American rule.

Early censuses

New Mexico underwent several censuses during its Spanish colonial and Mexican periods. But genealogist Francisco Sisneros tells us that these earliest counts were few in number, usually poor in quality and irregular in intervals, occurring in 1750, 1790, 1830 and 1835. Of these four, only the Spanish census of 1790 was done well.

The Catholic Church kept far better records based on its sacramental records of baptisms, marriages and burials. Sisneros says that genealogists rely on church records because they were mostly well-kept and, given the priests’ good penmanship, relatively easy to read.

The United States conquered New Mexico in 1846, leading to our first U.S. census in 1850. As a U.S. territory, New Mexico could not send a voting representative to Congress, but the census was crucial to New Mexico’s goal of becoming a state. A territory needed at least 60,000 residents to qualify for statehood.

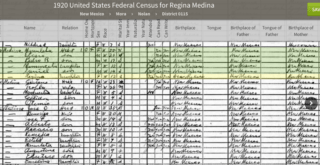

A family of 16 being counted for the U.S. census.

Submitted photos

The first territorial census was a dismal failure. Most of the census takers were Anglo newcomers, not familiar with either New Mexico’s geography or even the most common Spanish surnames.

Census takers did relatively well with large, more concentrated populations, especially Santa Fe. But most New Mexicans lived in the countryside and were difficult to find. Not yet trusting their new rulers, many New Mexicans probably did their best not to be located or counted for fear of being taxed or otherwise bothered by the new government.

If located, people pronounced their Spanish names and census takers wrote them down phonetically, with wide variations. Chavez, the most popular name, was spelled three different ways: Charbis, Charvis and Chavis. Padilla, Montoya and Trujillo were each spelled six different ways. Jaramillo was spelled 13 ways, from Haramio to Xaremillo.

With all these problems, the census reported that there were 61,547 men, women and children living in New Mexico in 1850. A decade later, a more accurate census listed 93,516 residents of New Mexico.

Plight of the census takers

Taking the census did not become much easier over time. First, census takers, known as census enumerators, had to be recruited and trained. As in 1850, language could be a barrier, with bilingual enumerators often receiving extra pay for their appreciated linguistic skills.

Census takers in Valencia County were similar in many ways, but different in others. In a sample of 10 enumerators in the censuses of 1910 to 1940, all were found to be Hispanic, nine were married or widowed and all had children living at home.

Their ages ranged from 29 to 60, and their occupations varied from a sheriff (Placido Jaramillo) and a retail store salesman (Isaias F. Baca) to a printer (Saturnino Baca) and a laborer (Federico Baca). We do not know their political affiliations, although it probably did not hurt to be a member of the dominant party (Republican in the censuses of 1910, 1920 and 1930, and Democrat in 1940) to secure this federal job.

Recruiting for this temporary employment could be difficult, especially when compensation varied and pay was often low. Urban census takers received 4 cents for every person they recorded on their forms in 1920.

Early census takers wore official metal badges to identify themselves.

A woman census taker in Santa Fe held the record for the greatest number of residents counted in a single day, 240, giving her $9.60 for her day’s labor (equal to $120 today).

Of course, corrupt census takers could pad their numbers to make more money than they deserved. Census takers caught in the act of fabricating records faced serious punishment for their misdeeds.

A census taker in Santa Fe found guilty of padding his count in 1900 received a four-year prison term as his sentence. After years of appeals, President William Howard Taft commuted the culprit’s sentence. The man never served a day of his life in prison.

Given the great distance between farms and ranches, rural census takers in 1920 were compensated by the day ($6) rather than by the number of people counted each work day. In 1940, a census taker took an entire day to get to a single rural home, occupied by a family of four.

Sometimes census takers lost more money than they earned. Because it was common knowledge that census takers left home to do their work, some thieves took advantage of their absence to stage robberies.

A Santa Fe newspaper reported that when Adolphus Algiers returned home after working on the census in 1880, “he found that in his absence he had been deprived of a lot of lumber” bought, no doubt, with his anticipated earnings as a census taker.

Bogus census takers canvassed neighborhoods to gain entry into homes for illegal purposes, usually involving property crimes. Census officials cautioned citizens of this hazard, while also warning pretenders that they could face $1,000 in fines and three years in prison for impersonating census enumerators in 1960.

Census officials tried to relieve public fears of phony census takers by urging people to ask census takers for proper identification. Early census takers wore metal badges. More recent census takers wear red, white and blue badges with photo IDs, the words “Census Enumerator” and the blue seal of the Department of Commerce.

Finding folks to count

Some populations were easy to count. In 1870, for example, census takers could easily count 172 officers and men stationed in a single location, Ft. Union. In another example of an entire institution reporting its population, the state penitentiary in Santa Fe reported 700 inmates in 1940.

Of course, institutions such as forts and prisons could gain or lose large percentages of their populations given changing circumstances. The number of soldiers at Ft. Union declined quickly between the census of 1870 and the count of 1880, sliding from 172 to 49 officers and men, largely due to the end of the Indian wars in northern New Mexico. The fort was closed in 1891.

Whole towns could experience similarly dramatic fluctuations. Loma Parda, located within walking distance of Ft. Union, was a sleepy village of 80 residents in 1860 before it grew into a bustling town of 372 by the census of 1870. Unfortunately, most of this increased population included newcomers who catered to the soldiers’ vices, from liquor and gambling to prostitution and violence.

Known as the “Sodom on the Mora River,” Loma Parda’s boom town population declined in direct proportion to Ft. Union’s decline in numbers and demands. The town and the fort each lost about 120 people from 1870 to 1880.

Other towns were just as vulnerable to rapid changes in population. The coal mining camps of Dawson, near Raton, and Madrid, near Santa Fe, boomed in the 1920s but became ghost towns by the 1950s when oil and gas replaced coal as the country’s major sources of energy.

Los Alamos was little more than a boys school and a small agricultural community in 1940. By 1950, it had become an atomic research center with such a large population (10,476) that it became the first new county established in New Mexico since 1921.

A typical census taker collecting information in the early 20th century.

Unlike folks in forts, prisons and boom towns, most New Mexicans residents were more difficult to find, no less count. Long before there was GPS, good maps were rare and often outdated. Rural terrain was often rough, with poor roads that were frequently covered in sand, mud or debris. And that’s assuming that there were roads to a person’s dwelling.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, a poor man and his two sons lived in a cave outside Las Vegas. The three residents were quite cooperative, but it took the census taker a good deal of effort to climb a steep cliff to reach the family’s unique quarters.

Census takers relied on every conceivable form of transportation to complete their rounds. Most walked or drove their cars or trucks. Some rode horseback, often accompanied by pack mules to carry their supplies long distances. Camping under the stars on extended trips was not unheard of.

Beasts in waiting

Once near a dwelling, census takers had to face any number of so-called domestic animals. Understandably, census takers feared vicious dogs most of all. But sometimes dogs were the least of their concerns.

In 2000, a census taker snuck by a dog and was almost to the door of a mobile home when a turkey came charging around a corner with his feathers flaring. Somehow, the census taker shooed the turkey away, using her census forms as a make-shift means of defense. Unperturbed, the dog never flinched.

In another instance, neighbors warned an Albuquerque census taker that a resident on their block was a lady wrestler who kept a lion tied to her front tree. Coming to the wrestler’s house, the census taker (on her first day on the job) saw the lion tied to the tree but noticed that there were no humans at home.

The brave census taker returned later, but never saw the lion again and never encountered its lady wrestler owner. We’ll never know if the woman would have insisted that her lion be counted in the census, as one man did when he claimed that his pets were legitimate members of his family.

Filling out required forms

A census taker’s trials had just begun when he or she arrived and began to fill out census forms inside a home. Identifying the head of each household would seem to be a simple matter, but there were snags.

In 1960, a woman in Santa Fe told the census taker she was the head of her household, adding, “My husband is just the figurehead.”

Identifying the head of a household was also difficult a decade later when a census taker visited a hippie who said he was the head of the household and the woman he lived with was the “friend of the head of the household.” Predictably, the woman’s 5-year-old daughter was listed as the “daughter of the friend of the head of the house.”

As in the census of 1850, names could be challenging as well. In 1940, a census taker on the Navajo reservation complained that translated Navajo names were often too long for the small space provided on that year’s census form. How was he expected to fit names like “The Man Who Walks Behind His Wagon” or “The Blind Daughter of the Third Wife of the Man Who Walks Behind His Wagon?”

Census takers complained that some individuals provided far too much information. In 1930, a census official implored the public to answer questions succinctly, adding that census takers didn’t “give a whoop about your personal affairs.”

They certainly didn’t need to ask the question about how long a person lived in a house and learn from an elderly person that she had helped build her family’s adobe house when she was only 8 years old. With answers like these, filling out the census form took as long as 2.5 hours when it normally took only about 45 minutes to complete.

A sample page from the 1920 U.S. census.

Although it was illegal to give false information, some people fibbed, especially when it came to the question of age. Women were particularly reluctant to state their age. In 1890, a newspaper in Santa Fe reported that women whose birthdays came just after the census date thought the census taker “just a horrid creature for not coming around earlier.”

According to a joke in 1900, when a census taker asked a woman her age, the woman asked, “Did the woman next door give her age?” “Certainly,” said the census taker. “Well,” replied the woman, “I’m two years younger than she is.”

Another joke about women and their age made the rounds during the 1960 census. According to this tale, the mother of a 22-year-old daughter insisted that she was 29. When the census taker pointed out that this was biologically impossible, the mother admitted, “I’ve lied about my age so long, I’ve forgotten how old I really am.”

Newborns posed other problems. In 1950 a husband had just finished giving a census taker information about himself, his wife and their 2-year-old daughter when a midwife appeared from a back room and announced the birth of a 6-pound baby boy. The census taker quickly updated his form.

Tragic deaths could alter the census just as quickly. In 1920 a census taker visited a Navajo hogan in northwest New Mexico only to find that all seven members of the family that lived there had died of the flu.

This census taker had arrived too late to be of help to the stricken family, but in 1940 another census taker arrived just in time to rescue a man whose Denver apartment had accidently filled with gas. After sending for medical aid, Madeline Elberger dutifully left a note that she would return later when the man had recovered.

A similar rescue occurred in Boston, but in this instance the census taker insisted on gathering information about the victim before he was taken off to the hospital.

Refusing to cooperate

While most New Mexicans cooperated with census takers and their questions, others resisted. Some people were simply mad at the federal government for its policies, its taxes or, as in the case of the census, its supposed infringement of their privacy.

An Albuquerque census taker encountered one such protester in 1970. When the census taker approached the man’s house, she was encouraged to see an American flag flying prominently in his front yard. Surely, this proud citizen would be happy to answer her questions. Instead, he refused to cooperate, saying that as a U.S. citizen he had a right to his privacy.

The census taker went by the flag waving man’s house several times but he did not change his mind even when she pointed out the value of the national census.

Then one day, the census taker went by the reluctant man’s house and noticed a white flag where the American flag had long flown. Asked about the white flag, the man said it meant that he had changed his mind about the census and he was ready to “surrender” and answer all her questions.

Census takers have also encountered people with unusual behaviors or long-lasting vices. In 1960, a nudist colony barred a census taker until he shed his garments. The nudists willingly revealed the naked truth about their lives once the census taker had completely disrobed.

In 1950, a man was so “dead drunk” when a census taker went by his house that he was unable to answer her questions. When the census taker patiently said that she’d come back the following week when he was sober, the man replied, “No, go ahead and ask me the questions now. I’ll be just as drunk next week as I am now.”

Census officials often considered hippies of the 1960s and 1970s to be their greatest challenge. In 1970, about half of New Mexico’s hippie population lived in “communal villages” such as New Buffalo and Morning Star near Taos. The other half (numbering about a thousand) were more transient, living in temporary housing like tepees or converted school buses.

In the words of one census taker, “They move around a lot and it’s pretty hard to tell one from another. We just might count some of them more than once.”

Hippie names could be just as troublesome. In 1970, a census taker near Taos asked a hippie what his first name was. When the young man answered, “George,” the census counter asked for his surname. George replied that his surname was “Peace.”

Census takers faced Native American cultural challenges of other kinds. Navajo citizens considered it taboo to talk about themselves or even give their names, making it necessary to gather information from neighbors or other members of their households.

Some Navajos were particularly reluctant to share their information in the census of 1940 after the federal government had recently slaughtered thousands of their sheep and goats to halt overgrazing on the reservation.

If the government killed their sheep and goats, wouldn’t it kill identified people as well? These fears were especially understandable among Navajo who remembered how their ancestors suffered during the Long Walk, at Bosque Redondo and from other ill-conceived, often deadly, government programs.

Recent controversy

Questions regarding race, nationality and ethnicity have raised other questions and controversy over the last 50 years. Previously, Americans were asked to identify themselves as “whites,” “negroes” or “Mongols.” But many Hispanics, who had identified themselves as “whites” for lack of a better category on census forms, began to pressure the government to list other identities that they believed were far more accurate by the 1970s.

This year’s 10-question census includes three options regarding a person’s “heritage, nationality, lineage or country of birth”: Spanish, Hispanic and Latino in question No. 8. But question No. 9, regarding race, leaves Hispanics few good options among six choices: whites, African-Americans, American Indians, Asians, Pacific Islanders or “some other race.”

Additional controversies are tied to the question of immigration. A faction of Americans insists that the government ask if those who complete the census are U.S. citizens. Others vehemently disagree. As a result, the 2020 census does not include a citizenship question.

Census takers are also banned from asking such private questions as a person’s Social Security number, party affiliation, banking account or credit information. Anyone asking for such information is probably operating a scam.

Importance of the U.S. census

Census information is first and foremost important in determining how many representatives New Mexico can send to Washington, D.C., to represent us in the House of Representatives. With more than two million residents, New Mexico is on the verge of having a fourth representative if we maintain this “critical mass” in this year’s census.

A good, accurate census is also important because these numbers are vital in determining the eligibility and funding for valuable federal programs in a poor state like New Mexico. An undercount in 2010 cost New Mexico millions of dollars in health, education, child programs, road repair, fire safety and other vital programs, few of which New Mexico could afford completely on its own. Valencia County alone will lose more than $22 million over the next decade for every 1 percent undercount.

Of all the states in the country, Alaska and New Mexico were the two worst in responding to the census in 2010. The five census tracts in southern Valencia and northern Socorro counties are reportedly the hardest to count and most grossly under-counted sections in the entire United States.

New methods have been developed to facilitate census taking in 2020, especially during the COVID-19 crisis. It is possible to complete census forms online (my2020census.gov), through the mail or by phone (1-844-330-2020 for English; 1-844-468-2020 for Spanish). The third of the state’s population that lack internet access can receive phone assistance by calling the Belen (966-2600) or Los Lunas (839-3850) public libraries.

There will still be census takers, but they will be fewer in number and only be contacting those who have not completed their forms online, through the mail or by phone. Delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the whole process will be completed by Oct. 31.

So please be kind to our census takers if they come by. Be sure to tie your dangerous animals in the backyard, fly only white flags when you see your census taker coming, tell the truth about your age (and everything else) and definitely don’t take your misgivings about the federal government out on our census takers.

Census takers are not government spies, enemy agents or neighborhood busy-buddies. They are simply dedicated citizens who deserve our cooperation as they make their rounds and complete their important task for the benefit of us all.

Richard Melzer

Biographer

(La Historia del Rio Abajo is a regular column about Valencia County history written by members of the Valencia County Historical Society since 1998.

The author would like to thank genealogist Francisco Sisneros, Belen Mayor Jerah Cordova, Belen public librarian Kathleen Pickering, Los Lunas public librarian Cynthia Shetter and Dana Bowley, of the Valencia County Complete Count Committee, for their kind assistance.

Opinions expressed in this and all columns of La Historia del Rio Abajo are the author’s alone and not necessarily those of the Valencia County Historical Society or any other group or individual.)

Richard Melzer, guest columnist

Richard Melzer, Ph.D., is a retired history professor who taught at The University of New Mexico–Valencia campus for more than 35 years. He has served on the board of directors of the Valencia County Historical Society for 30 years; he has served as the society’s president several times.

He has written many books and articles about New Mexico history, including many works on Valencia County, his favorite topic. His newest book, a biography of Casey Luna, was published in the spring of 2021.

Those interested in joining the Valencia County Historical Society should contact Dr. Melzer at [email protected].