Over the centuries, the Rio Abajo and, in particular, Valencia County have been rich cultural melting pots. It was a nexus of Tiwa, Piro, Tompiro and Comanche tribes. It has welcomed people from Spain, Mexico, Japan, Germany, France, the United States and Africa and religions from Protestant to Catholic to Nativist.

Names such as Becker, Togami, Huning, Tondre and St. Vrain have mixed with Chavez, Otero, Luna and Smith. However, there is one group of individuals whose contributions have not been as carefully described.

These are the German Jewish immigrants and their families who were important merchants and businessmen in the area during the 19th and early 20th centuries. I would like to focus on three of these families — the Sachs, the Kempenichs and the Neustadts.

Submitted photos

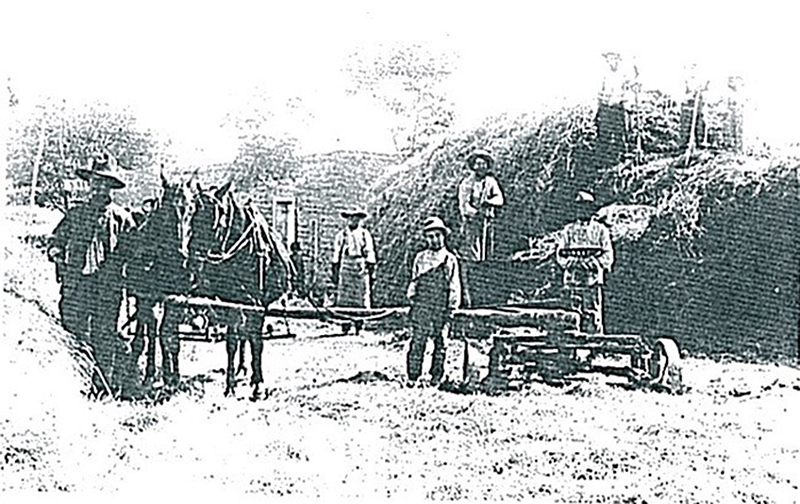

The Sais family baling hay in Los Lentes.

The family of Moses Martin Sachs

Moses Martin Sachs was born in Bavaria (some notations say Prussia) in 1823. He emigrated to the United States with several family members in 1832 and arrived in Valencia County sometime in the late 1840s. The 1850 census shows him as a single man with a total net worth of $500 (equivalent to about $25,000 in today’s dollars) working as a merchant in Los Lunas.

His household includes a servant and a laborer, quite a success for someone who is just getting his feet on the ground in a new country. He had converted to Catholicism sometime around 1852 to marry a local woman named Maria Gertrudis Baca. By 1860 the couple had two daughters, Josefina age 7 and Carolina age 6.

Unfortunately, by 1857 Sachs had overextended his business and became insolvent. He spent the next three years working to pay off his creditors. He sold his store to Ehrhard Franz, Franz Huning and Franz Huning’s brother, Carl. By 1862, the store was known as F & C Huning Co. mercantile. Sachs and his family moved to Belen, where they lived with his wife’s family for a time.

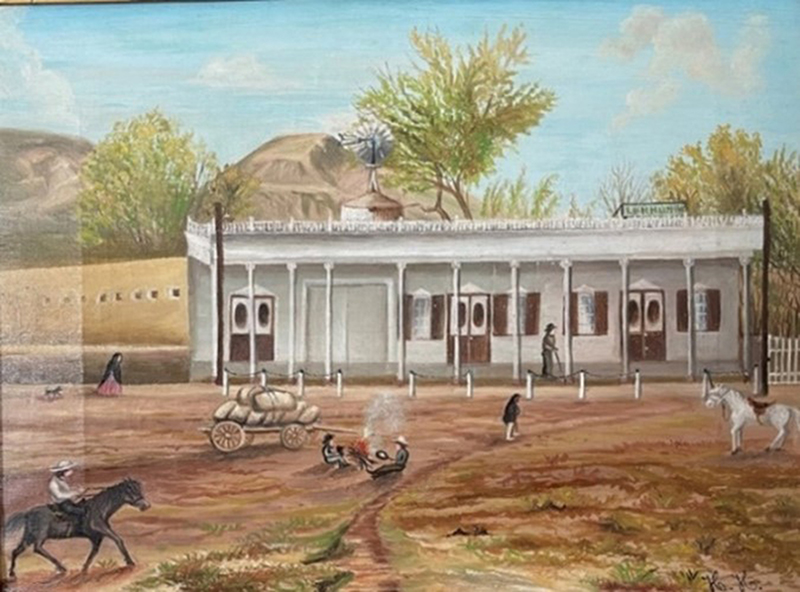

An early image of the Huning house.

By 1860, he appears to have re-established himself as a merchant. The census lists him as living with his wife, Gertrude, three daughters, and a servant. He apparently managed to liquidate his previous indebtedness, since he is listed as having real estate valued at $1,000 and a total estate worth $3,000 (comparable to a net worth of about $150,000 in today’s dollars), an increase of a factor of 6 in previous 10 year.

Historian Rico Gonzales points out that the mid-19th century economy in New Mexico did not rely on substantial cash transactions, operating largely on a barter basis. While continuing to deal with the 261 residents of Los Lunas on this basis from his local store, which would become the Huning House in Los Lunas, Sachs took on two more lucrative occupations to further increase his bottom line — he was appointed postmaster in Los Lunas on Nov. 6, 1855 (serving until November 1857 when the post office was apparently closed) and again on Dec. 5, 1866, (serving until August 1867), and he became the dedicated forage agent for the U.S. Army in the area.

As a forage agent, Sachs was responsible for providing hay, corn, barley and oats to the military, as well as

… promoting the general interest of the United States by protecting government property, recovering stolen or stray animals and “indisposed” government employees, providing soldiers and employees with means for cooking their meals, and circulating supply advertisements for the quartermaster’s department.

Hay was of particular importance to the U.S. Cavalry. Hence, forage agents were critical to the success of Army operations in the Southwest. According to historian Ron Ariel,

Hay was a linchpin of the early industrial energy regime. It was the primary fodder for working horses, who became more rather than less important over the 1800s. Though largely ignored by historians, hay was of comparable value to cotton and wheat in the nineteenth-century United States.

Submitted photos

A view of the Peralta portal as it was burning in 1954.

In 1852, the War Department had established a post in Los Lunas for “waging campaigns against Navajo, Apache, and Comanche Indians” and for the protection of settlers in the area. The post was occupied by soldiers from the First Dragoons, who were commanded by Capt. Richard Stoddard Ewell, a man who would later achieve some notoriety as a Confederate general during the Civil War.

Sachs’ ability to provide the necessary supplies to Ewell was good enough that when Ewell was relocated to Tucson for nine months in 1856, he continued to use Sachs as his supplier.

Despite his appreciation for Sachs as a supplier, Ewell appears to have viewed him with some racist sentiment. In a letter to his brother, Ewell remarked, “Today I have been pestered by a Dutch merchant Jew,” clearly referring to Sachs who, as noted earlier, was a Catholic. (This is the only direct anti-Semitic reference that has surfaced during our rather extensive studies of Rio Abajo history.)

Sachs’ fortune had continued to improve. By the time of the 1870 census, he is listed as a farmer, still living in Belen with his wife, Maria. They now have six children — having added two sons, Benedict and Henry, and another daughter, Luisa. The census shows his net worth as $7,000 (about $260,000 in today’s money).

He and his family are still in Belen in 1880, still listed as farmers, but the enumeration does not list their net worth. Interestingly, the census enumerator who visited the Sachs’ household in 1880 is another of our local Jewish merchants, Simon Neustadt.

Sachs died sometime between 1880 and 1885 and is probably buried in an unmarked grave in or near the Sachs family plot in the Belen Catholic cemetery.

All of Sachs’ children and most of his grandchildren continued to live in Valencia County. Even today, several of his great and great-great-grandchildren still live in Belen. Unfortunately, no images of Moses Sachs have been discovered.

The family of Abraham Kempenich

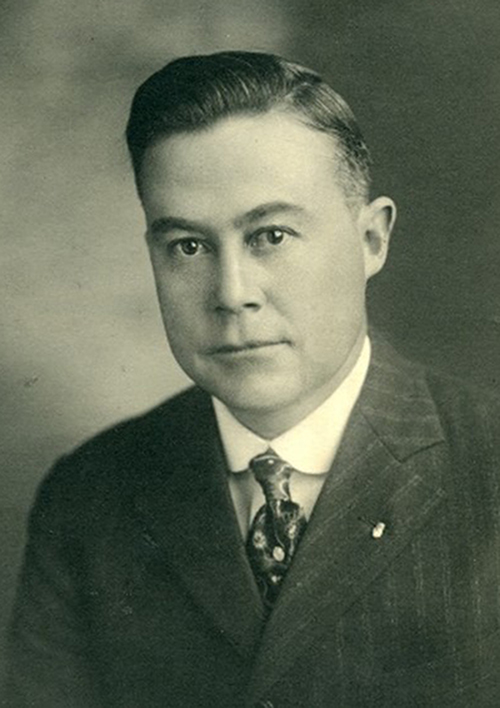

Abraham Kempenich was born in Germany on July 2, 1854, and emigrated to the United States in 1892 with his wife, Jennie, and their two sons, Paul and Eugene.

Kempenich purchased a store across from the church of Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church in Peralta from Higinio Sanchez, a local merchant.

Peralta church in 1916 with steeples designed by Kempenich.

In 1902, Father Ralliere, the priest at Tomé and, therefore, the priest responsible for Tomé’s mission church in Peralta, asked Abraham to design steeples for the then-flat-roofed church. Unfortunately, he did not live to see his design installed, since Ralliere waited until 1916, 11 years after Abraham’s death to complete the installation.

Abraham was the postmaster in Peralta from October 1890 until his death in 1905 and served as river commissioner (the local person in charge of flood protection) for a period. His sons, first Paul and then Eugene, took over the postal responsibilities after their father’s death until the property was purchased by Henry Wortman, who continued to serve as postmaster until 1944.

Abraham was a very prominent merchant in the area as attested to by the frequent mentions of his visits to Albuquerque in the society and “goings on” columns of the Albuquerque Journal and the Albuquerque Citizen. He was also a member of the Albuquerque Elks Lodge.

Abraham and his family were active with Congregation Albert in Albuquerque, and he was buried in the Jewish section of Fairview Cemetery in Albuquerque after his death on Aug. 19, 1905.

After Abraham’s death, his wife, Jenny, and two of their three sons, Paul and Eugene, ran the store. Unfortunately, Jenny was destined to bury both sons.

Peralta church in 1900 with a flat roof.

Paul fell victim to the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic, and on the morning of Oct. 8, 1921, Eugene was found lying beside his bed, wearing a pair of silk pajamas, with a revolver under his hand, dead from a single gunshot wound to his back.

After immigrating with his family, Eugene had become a prominent New Mexico businessman and politician. He owned a trading post in eastern Arizona, had been active in Sandoval County politics, and was serving on the State Highway Commission when he was shot.

The circumstances surrounding his death suggest that sometime in the early afternoon of Oct. 7, Eugene had either seen, met or talked to someone who had threatened him. He apparently rushed home from a previous appointment in Moriarty, but when the threat did not immediately materialize, he changed into his night clothes and went to bed, keeping a revolver under his pillow. Sometime during the night, he was shot as he slept.

Valencia County Sheriff Joe Tondre

Despite the best efforts of Sheriff Joe Tondre, the murder was never solved, although the rumor was that he was shot “because of highway business.” Consistent with the earlier observation regarding Moses Sachs, there was no implication of anti-Semitism mentioned in connection with the crime.

Eugene is buried in the Congregation Albert cemetery in Albuquerque.

With two of her sons dead within three years, Jenny sold the property to Henry Wortman, a former German soldier who had been employed by the Kempenichs (and one of the two men who had found Eugene’s body). Together with his family, Wortman ran the store and acted as postmaster until 1944.

Submitted photos

Abraham Kempenich’s grave marker in Fairview Cemetery.

By the early 1950s, the plaza across from the church included Wortman’s store, a bus stop, the Post Office, a small bar on the south end and a Sinclair gas station with two pumps. The entire building was stuccoed in white with red trim.

The portal burned down in the spring of 1954 and was not rebuilt. Today, a collision repair shop and vacant restaurant stand approximately where the original building used to be.

(This story will be continued in the next edition of La Historia.)

(La Historia del Rio Abajo is a regular column about Valencia County history written by members of the Valencia County Historical Society. The author of this month’s column is John Taylor, a retired engineer from Sandia National Laboratories and board member of the Valencia County Historical Society. He is the author or co-author of 25 books on New Mexico. Opinions expressed in this and all columns of La Historia del Rio Abajo are the author’s only and not necessarily those of the Valencia County Historical Society or any other group or individual.)