For most people, the COVID-19 pandemic is wearing a mask in public, extra hand washing and standing in lines to get into the grocery store.

For others, it’s eight hours or more on their feet in the New Mexico summer sun for months on end testing people for the virus. It’s being the only and possibly last human contact a patient dying due to COVID-19 has.

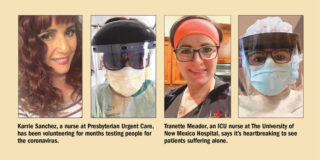

When the virus hit New Mexico in March, Karrie Sanchez, a Los Lunas nurse who works at a Presbyterian Urgent Care in Albuquerque, was one of the first people to volunteer to work the massive test site eventually set up at Balloon Fiesta Park.

“At the beginning, Presbyterian was one of the first places that put up a test site. One of our urgent cares was closed and made into a site and it evolved from there,” Sanchez said. “I worked the Fiesta site since May. I thought, ‘Well I’m going to volunteer. I want to see what this is all about.’

“I felt comfortable because I knew I had all the gear on. Not like now, with people just walking in to the clinic. You’re not in full PPE and the people who come in might be asymptomatic or if they seem to have symptoms, it might just be congestion. You just don’t know.”

When the Fiesta Park COVID-19 test site first opened, Sanchez said the line of cars waiting was often backed up to Interstate 25, almost a mile away.

“I just remember it was very hot. One day, I think we did it it was 105 degrees. We were out there for eight hours a day,” she said. “The maximum I remember we did was 800 in a day. It finally slowed down to an average of 500 (a day.)”

While the site finally implemented a “snake” formation for the line, so more cars could wait in the park itself, that didn’t mean the wait was any easier, Sanchez said, but wait times were still up to six hours.

“People were running out of gas, needing food because they were diabetic,” she said. “That was a difficult time. At the beginning, it was ‘OK, we need to get as many tested as possible to see where the numbers are.’ We really didn’t even know how it was contracted as much as we know now.”

According to the CDC website, the novel coronavirus, which causes COVID-19, most commonly spreads between people who are in close contact with one another, within about 6 feet.

It spreads through respiratory droplets or small particles, such as those in aerosols, produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, sings, talks or breathes.

These particles can be inhaled into the nose, mouth, airways, and lungs and cause infection. This is thought to be the main way the virus spreads.

There is growing evidence that droplets and airborne particles can remain suspended in the air and be breathed in by others, and travel distances beyond 6 feet.

For example, during choir practice, in restaurants or fitness classes. In general, indoor environments without good ventilation increase this risk.

“We are exhausted. I think all health care workers are truly, truly exhausted,” she said. “We’ve been working hard since day one. We’re scared of the uncertainty.

“This has been overwhelming for a lot of people. I have a 13 year old who had asthma as a baby. My elderly grandmother has diabetes. I don’t see her daily, but …”

For 6 1/2 years, Tranette Meador, a Los Lunas resident, has been a nurse in the trauma thoracic cardiac intensive care unit at the University of New Mexico Hospital.

“In the spring, when COVID hit, it was an overwhelming feeling going to work just because there were so many unknowns of the virus,” Meador said. “I have small children at home. I didn’t know what I could potentially bring home to them and my husband.”

As more became known about the virus, circumstances quickly changed for Meador — she and her coworkers were screened going into work every day with temperature checks and questions about whether they could have been exposed.

Visitors for ICU patients, whether COVID-19 positive or not, immediately became a thing of the past.

“There were a lot of phone calls, FaceTime, Zoom,” she said. “It’s made it really, really challenging. The only people they are seeing are health care workers.”

When she’s in the room with her patients, Meador provides medical care as well as physical, human touch.

“I’m constantly talking to them regardless of them being sedated. You explain everything you’re doing — whether it’s oral care every two hours, eye drops, you’re constantly (adjusting) medication,” she said. “Even though they are sedated, they can still hear you. Some patients will mouth to you over their breathing tube. A lot of times we just ask yes or no questions, so they can nod or shake their head, give a thumbs up.”

Meador said COVID patients are “much, much, much sicker than a flu patient,” and require nurses to spend a lot of time in a room.

“Especially if we’re having to ‘prone’ them, putting them over on their belly. It takes a team to do that,” she said. “We’re constantly coordinating our time management, as well as making sure that all the (other) patients are getting the care they need.”

When COVID-19 patients first began coming into the ICU, Meador said her husband asked her to quit.

“I absolutely love my profession. My coworkers need me. My patients need me. He’s grown a lot this year,” she said with a small chuckle.

When she isn’t working, Meador said her two children are her light and her outlet.

“That’s what brings me joy, as well as being there with my coworkers, helping them and talking to them, knowing we’re all going through the same feelings and emotions,” she said.

One of the hardest things she’s had to do is “train” her children — 5 years old and 17 months old — to not run up and give her a hug when she gets home from work until she’s taken a shower.

“It’s a terrible feeling as a mom to see your babies crying because they just want a hug,” she said. “And I can’t because I’ve been taking care of COVID patients.”

So far, Meador has only had to be tested once, last week after being exposed to COVID-19 during an aerosolized procedure on a patient.

“I was notified, and six days after, I woke up very congested, head pounding, my upper back killing me,” she said.

She notified the hospital and she was moved off the schedule and tested immediately.

“It came back negative — thank God. I’m a breast-feeding mom and a lot of factors came into play so quick,” she said.

Meador uses the words “overwhelming” and “heartbreaking” often — the first to describe the overall impact of the virus and the second in empathy for families cut off from loved ones.

“Family is a huge part of the healing process, so it’s extremely hard not having family around,” Meador said. “The biggest thing I can stress is take it seriously — wear a mask and wash your hands.

“This is very serious. Everybody compares it to the flu. The flu is not as deadly as this virus is. I had a coworker lose her father and that hit really close to home for me. Take this seriously,” she said. “Wear a mask, wash your hands, social distance as much as you can until they figure out a vaccine or how to properly treat this. It’s trial and error right now with what’s working and what’s not.”

Sanchez asked the public to take the time to research where they need to go for care depending on the symptoms they have.

“If you can tolerate the symptoms, stay home. If you don’t have shortness of breath or trouble breathing, stay home,” she said. “If you want to get a test, get an appointment. It gets really difficult when you are mixing all types (of patients) at an urgent care. You have little old ladies with a UTI, then there’s a COVID patient with sniffles and a sore throat.

“Stay home. Calm down. Most people are surviving; what everyone doesn’t know is how they’ll tolerate it. If you test, do it at a test site and if you have it, stay home.”

Julia M. Dendinger began working at the VCNB in 2006. She covers Valencia County government, Belen Consolidated Schools and the village of Bosque Farms. She is a member of the Society of Professional Journalists Rio Grande chapter’s board of directors.