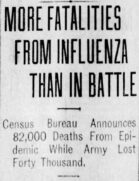

Nearly 102 years ago, the United States faced the worst epidemic in our nation’s history. The Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 killed more than half a million Americans and an estimated 20 million men, women and children worldwide.

More Americans died of the flu than in all of our country’s wars of the 20th century combined. No one seemed safe, no matter where a person lived or how hard a person tried to avoid the dreaded disease.

Not even the residents of relatively isolated Valencia County were immune once the flu germ entered New Mexico in October 1918 at the very end of World War I.

Trying to avoid the flu

Residents of New Mexico and Valencia County tried various measures to avoid the flu in this public health emergency. Gov. Washington E. Lindsey ordered the closing of all schools, courts, churches and other public gathering places. All business activity came to a standstill.

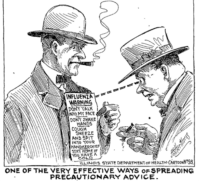

Health officials warned people to avoid excessive eating, too much work, unventilated rooms, coughing or sneezing without handkerchiefs, spitting on the ground and drinking whiskey.

Illinois Health News, October 1918

Despite the latter advice, some locals believed that drinking moonshine liquor was a good way to prevent — or even cure — the flu. Martin Quintana recalled his father preferred this method, although his mother did not; true ladies did not drink, no matter what the emergency.

Other remedies were attempted to no avail. Some turned to curanderas, but not even traditional herbs and treatment helped in this crisis.

Patented medicines such as Hamlin’s Wizard Oil and standbys like Vicks Vaporub falsely claimed to prevent or cure the flu. Some even resorted to eating lots of onions; at least no one would come near them to spread the disease.

Although millions of people in the United States wore surgical masks voluntarily, some communities, including Taos, required their residents to wear this protection. At least one store in Albuquerque advertised the sale of chiffon veils in all colors and patterns as a fashionable alternative to plain white masks.

A vaccine was developed, but it was too late and too little to be of much help, especially in little communities like Belen, Los Lunas and Tomé.

The victims

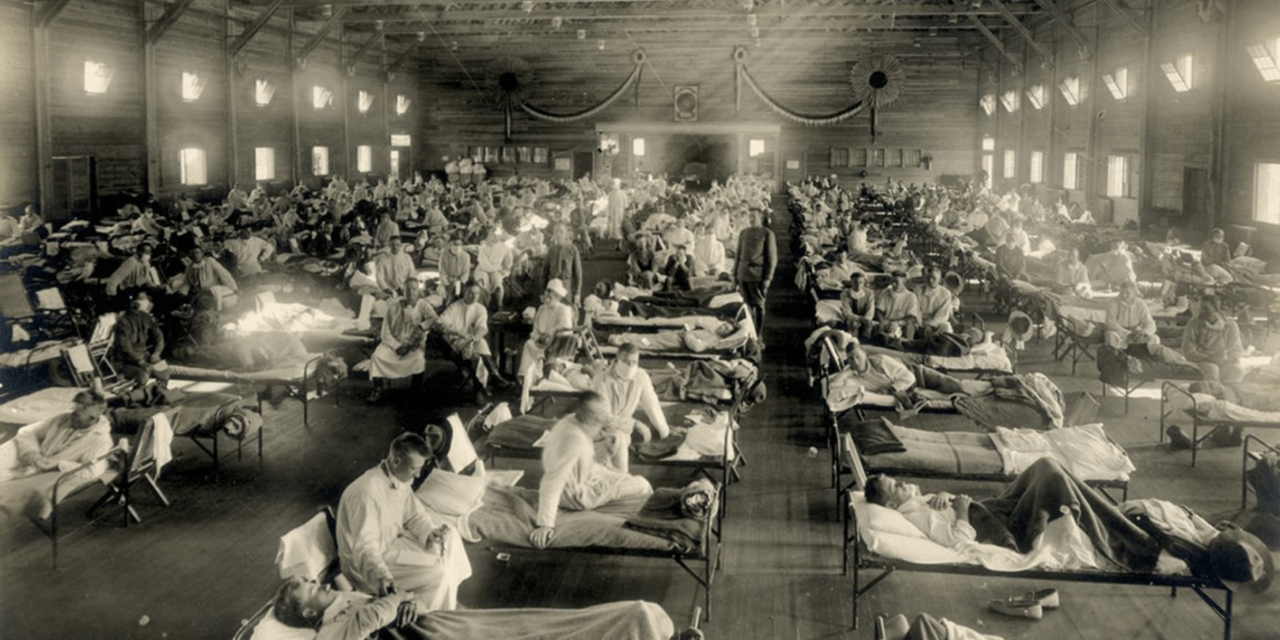

Dozens in Valencia County caught the disease, with a high percentage dying of influenza or pneumonia within hours. Like all railroad towns, Belen was especially vulnerable. Railroad workers and passengers could easily bring the flu germ from infected areas across the nation.

Eduardo Abeyta, a worker at Belen’s roundhouse, died in the epidemic, leaving his wife a widow with five young children to care for. Frank Barror, a locomotive engineer, survived the epidemic, but his wife, Lucy, died of the flu at their home on Third Street and Ross. Another railroad worker, Fred Hawkins, lost both his wife and son.

Courtesy of the Albuquerque Journal

On Oct. 10, 1918, the Belen News printed a long list of stricken residents, including the bookkeeper and cashier at the John Becker Store and so many employees at the First National Bank of Belen that the bank was forced to close its doors.

Transported by wagon, many flu victims were brought to the local grammar school to receive care. Kind neighbors often brought soup to the sick in their homes, only to catch the flu themselves.

Dr. Samuel Williamson came down with the illness, leaving Dr. William Radcliffe, in Belen, and Dr. William Wittwer, in Los Lunas, as the only physicians well enough to handle the onslaught of local patients in need of attention. Years later, Dr. Wittwer identified the flu epidemic as the worst medical crisis of his career, spanning more than six decades.

Health personnel arrived from out of town to help. The Santa Fe Railroad brought Dr. David Knapp, of Santa Fe, to look after railroad employees and assist Drs. Radcliffe and Wittwer as much as possible.

But a whole army of doctors and nurses could not have stopped the flu and its deadly assault. Usually, at least one member of every family caught the flu, increasing the odds that others in each family would grow ill, too. According to one estimate, more than half of Belen was sick. As many as 10 residents on a block in Belen reportedly died on a single night.

Everyone was susceptible but, in an odd quirk of fate, those in the prime of their lives fell victim and died most often. The average age of those who died in Belen was 19.1. One of the authors, Oswald G. Baca, lost both his maternal grandmother, Rebecca Armijo Sanchez, age 22, of Jarales, and his paternal grandmother, Luz Romero Baca, age 30, of Los Trujillos. They died in October, the worst month of the crisis.

Church bells rang day and night to announce the passing of more and more residents. Belen’s two hearses, a car and a horse-drawn buggy, were kept busy, with the car reserved for the wealthy and the buggy used by the poor. Coffins could not be built fast enough to meet the demand.

Alex Castillo, who was 18 in 1918, recalled that with the Catholic church closed, the dead were “rolled past the church for a brief blessing, then went right on to the cemetery.” At the cemetery, grave diggers were hard to find because so many people were sick.

Belen and the surrounding settlements of Los Chavez, Los Trujillos, Jarales, Bosque and Pueblitos were among the hardest hit areas in all of New Mexico. Burial records at Our Lady of Belen Catholic parish show an astounding 122 burials during the month of October 1918, for an average of four per day.

Fr. Antonio Cellier recorded a total of 256 burials at the Belen Catholic cemetery in 1918. For comparison, in the entire year of 1917, there had been a total of 67 burials; in 1919 only 58.

The epidemic ended but the mystery remains

Thankfully, the flu subsided as quickly as it had begun. Much of the epidemic remains a mystery to this very day. Even its name, the Spanish flu, is a puzzle because the epidemic did not originate in Spain or any other Spanish community.

Evidence points to its origin at an Army camp, Camp Riley, Kan. The flu was doubly mysterious because it struck in the fall, while most flu seasons are in the winter months of January and February.

All we know for sure is that the epidemic hit with incredible speed in the last days of the first World War, showing no mercy to a world already ravaged by four years of violence and death. Some, like the preacher Billy Sunday, believed that the epidemic had been caused by so much sin and hate in the world.

The Las Vegas Optic asked if the Germans had caused the disease as part of their dreaded germ warfare.

Regardless of how or why it had come about, all were relieved that the pandemic had largely passed by late 1918. Tragically, more than 1,000 New Mexicans died of the flu and never enjoyed the new year or the post-war era of peace.

Lessons in the age of COVID-19

Although the Spanish flu of 1918 and the coronavirus pandemic of today are very different diseases, they share many similarities.

As with the flu, it is important to avoid all unnecessary travel, especially to areas with known cases of the virus. We must avoid crowds and practice social distancing. People should cover their coughs and sneezes and of course wash their hands thoroughly and often.

As in 1918, there is also no need for panic buying. If we overbuy or hoard, the most needy will go without and, given the law of supply and demand, prices will soar, making our economic problems even worse.

And there is certainly no need to panic and arm ourselves with weapons to defend our families and our property. With gun sales reaching unprecedented levels, one gun shop owner in Santa Fe has said, “This particular incident seems to have shaken people more than I’ve ever seen” in his 47 years in business.

The best advice we can take comes directly from an editorial in the Albuquerque Journal, written in the early days of the epidemic of 1918. The editorial was titled, “Don’t Let Flu Frighten You to Death.”

It read: “The editor of the Journal has just talked with some of the most prominent physicians of Albuquerque regarding the epidemic of ‘Spanish Influenza,’ and they all agree the greatest danger is from the panic of fear that is spreading over the country …

Oswald G. Baca

“Normally, according to pathologists, fear acts as a chemical stimulant … so that the man who shivered a moment before becomes as courageous as a lion …

“But there is a debasing and demoralizing fear … (when people) are frightened at … the horrors of their own imaginations. They … are the victims of their own frightened fancies.”

Despite the extreme severity of the Spanish flu, most New Mexicans did not give in to fear in 1918 and most survived. We must follow their example if we are to survive the coronavirus by obeying public health orders, making wise economic decisions and respecting law and order.

Richard Melzer

Biographer

When this storm passes, as even the pandemic of 1918 passed, those many who survive must be healthy, strong and wise enough to restart our individual lives and work together to rebuild the country we love.

(La Historia del Rio Abajo is a regular column about Valencia County history written by members of the Valencia County Historical Society since 1998.

Richard Melzer is an emeritus professor of history and Oswald G. Baca is an emeritus professor of microbiology at the University of New Mexico. The authors wish to thank historian Jim Sloan for his kind assistance.

Opinions expressed in this and all columns of La Historia del Rio Abajo are the authors’ alone and not necessarily those of the Valencia County Historical Society or any other group or individual.)

Richard Melzer, guest columnist

Richard Melzer, Ph.D., is a retired history professor who taught at The University of New Mexico–Valencia campus for more than 35 years. He has served on the board of directors of the Valencia County Historical Society for 30 years; he has served as the society’s president several times.

He has written many books and articles about New Mexico history, including many works on Valencia County, his favorite topic. His newest book, a biography of Casey Luna, was published in the spring of 2021.

Those interested in joining the Valencia County Historical Society should contact Dr. Melzer at [email protected].