Drivers traveling west into Belen on the Reinken Avenue. overpass seldom notice an old building to the north. The modern world seems to have passed the structure by.

But it wasn’t long ago that this old building was one of Belen’s main hotels, frequented by Santa Fe railroad workers and weary travelers who arrived by train from the nearby depot.

The building seems shrouded in mystery. Who had built and opened this hotel? Who owned the property over the years? How was it run? What caused its decline? And what does its future look like after more than a hundred years in existence?

Early years

Early maps of Belen show the property where the hotel stands was once used for very different purposes. About the turn of the 20th century, a building with Belen’s Commercial Club and Heyday Club, which included the town’s first bowling alley, once occupied the space beside the tracks. A small bakery stood just west of the Heyday Club, on North Second Street.

But the Heyday Club and its building were gone when a woman named Ruth Kuhn moved to Belen. Ruth had first come to New Mexico with her husband, Louis, and young son, Louis Jr. Traveling by covered wagon, the family entered the territory via Tucumcari and settled in Albuquerque’s South Valley by 1885.

According to family legend, Ruth ran the family farm while Louis worked as a blacksmith. All went well until Louis suddenly left, abandoning Ruth and her kids, Louis Jr. (born in 1882), Leo (born in 1887) and Stella (born in 1894). The couple apparently reconciled and moved to Baxter, Texas, with Ruth running a boarding house for a short while. But all did not go well, and the Kuhns separated once more.

Ruth Kuhn and her children, Louis Jr., Leo, and Stella, c. 1920

Submitted photos

Returning to New Mexico, Ruth settled in Belen, where she worked at and eventually owned a bakery and restaurant. Unfortunately, the only thing we know about Ruth’s enterprise is that the Belen News reported that someone had broken into her bakery and stolen some cakes, pies and an entire cash register late one Saturday night in 1911.

Despite this setback, Ruth apparently managed to save enough money to invest in a hotel. She might well have received financial assistance from the First National Bank of Belen. Women securing business loans was almost unheard of in those days, but there was a fortunate precedent in Belen.

Owned and operated by John Becker, the First National Bank had helped finance the building of the Belen Hotel, which opened in 1907. Always an astute businessman, Becker knew that hotels were needed with the completion of the Belen Cut-Off by the Santa Fe Railway. Bertha Rutz, a German nanny who had cared for the Becker children, ran the Belen Hotel for nearly 50 years.

Becker may well have financed the Kuhn Hotel because he recognized Ruth’s business skills and realized that Belen needed more than one hotel to keep up with the new railroad demands.

By 1913, the Belen city directory listed Ruth as a provider of room and board. By World War I, her business was well-established in a two-story hotel built on 5-foot deep footings and with 3-foot wide adobe walls.

Life in the hotel

Guests arrived at the Kuhn Hotel at all hours of the day and night. Once inside, they signed in at a registration desk next to the main entrance. Long before electricity and running water were installed, each new guest received two essential items — a kerosene lantern and a chamber pot.

Chamber pots were to be left outside of guest rooms each morning so that house maids could collect them, empty them and wash them with vinegar. Maids cleaned the rooms and provided fresh linen, as needed.

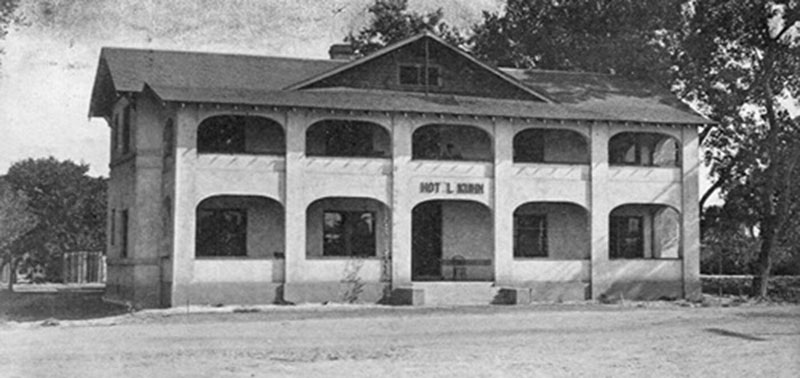

Hotel Kuhn postcard, c. 1920.

Ruth Kuhn provided one meal a day for her guests. Other customers paid 25 cents for her daily blue-plate special. Ruth was also known to make large bowls of iced tea and lemonade for her guests as they sat on the hotel’s balcony, especially as they watched town parades pass by on First Street.

In a more trusting age, the hotel’s front doors were left unlocked to allow railroad workers and call boys to come and go as their schedules required. Call boys knocked on the workers’ guest-room doors to summon them to join railroad crews, as needed.

Some guests were known to frequent notorious local bars until late at night. Ruth prohibited liquor in her hotel and did not tolerate guests she caught arriving after a night of drinking at places like the Railroad Club up the street. Many a guest was pushed out the door by Ruth armed with her favorite weapon, a broom.

In one famous incident, a guest returned to the hotel in an inebriated state. Getting past Ruth, the man began to climb the hotel’s stairs when an equally intoxicated, armed stranger ran into the hotel and shot the guest dead. Witnessing the fracas, Ruth ordered that the dead man’s body be dragged down the street and dumped in front of the Railroad Club. It seemed only fair that the place that had caused the problem be responsible for its results.

While Ruth banned alcohol on her premises, she reserved the right to indulge, at least when she was out of town. As the owner of a large, shiny Oldsmobile, Ruth hired a driver who drove her to and from her favorite place of amusement in Jarales.

Other owners

Born in Pennsylvania in 1862, Ruth was 67 and ready to retire in 1929. She put her hotel up for sale early that year, with a small, inconspicuous ad that ran in the Albuquerque Journal:

FOR SALE. Kuhn hotel, furnished. Belen, N.M. Address Mrs. R.C. Kuhn, Belen, N.M.

Once able to find a buyer, Ruth moved to Albuquerque to live with her daughter, Stella, and her son-in-law, Andrew W. Hinkle. Ruth suffered a stroke and died in Nov. 1940. Belen had lost a strong, independent business leader, one of the earliest successful women in Valencia County.

The hotel had various owners in the 1930s during the Great Depression. By 1940, it was sold to Bernard J. Vanderwagen, who completely refurbished the building, now referred to in the press as a “landmark in Belen.” Vanderwagen then leased the hotel to Garland M. Whittington, who also ran a boarding house on West Gold Avenue in Albuquerque. Signing a five-year lease, the Whittingtons moved to Belen and joined the local Chamber of Commerce. Unfortunately, 62-year-old Garland died at the hotel in October 1943.

Facing problems

The Great Depression of the 1930s was unkind to nearly every business, including hotels in Belen. Few Americans could afford to take vacations and the railroad often laid off employees or reduced their work hours.

To make matters worse, those who traveled increasingly used cars, buses and planes rather than trains. Hotels near train depots suffered, often to be replaced by motels along new highways.

Making a profit in the hotel business was a challenge before, during and after the Depression. Owners of the Kuhn Hotel looked for alternative ways to make money, with mixed results.

Guests at the Hotel Kuhn, c. 1925.

At some point, the hotel’s baths must have been rented out as public baths. Signs found in the basement advertised baths for 10 cents and shaves for 25 cents.

In March 1927, Dr. Gaines ran newspaper ads to announce that he would be at the Kuhn Hotel for six hours to consult with women about surgeries that did not require the use of knives. Hearing of this transient doctor and his suspicious procedure, many Belenites probably suspected a quack.

Local women also went to the hotel for beauty services in 1930. According to an ad in the Belen newspaper, ladies could call the hotel to make appointments for haircuts and settings offered at the hotel every Tuesday. Employees of the Albuquerque-Chicago College of Beauty Culture gave permanent waves for $5, equal to $75 in today’s money.

The Kuhn Hotel served as temporary headquarters for a rather suspicious sounding operation in early 1955. An ad in the Albuquerque Journal told readers that a Mr. McCoy would be available at the hotel to meet with “four neat appearing men or women living in Belen.” Mr. McCoy guaranteed that the fortunate four would be eligible for a “fast money-making proposition.” No experience was necessary, and no other details were provided.

A more legitimate businessman set up shop in the hotel in the 1950s and 1960s. A commercial photographer offered his skills for portraits taken on the hotel’s second floor. Many children receiving their First Holy Communions had their angelic photos taken at the Kuhn Hotel. The photographer also took pictures of graduations, proms and other special occasions.

Another talented person offered artistic services at the hotel. Despite the need for quiet with so many railroad workers trying to sleep day and night, a piano teacher gave lessons to local children. We do not know where the lessons were taught with the least impact on light sleepers.

A death sentence

The hotel had fallen on hard times by the early 1960s. A classified ad in the Albuquerque Journal was slightly more descriptive than the “for sale” ad that had run in 1929, but its wording was not optimistic: “Kuhn Hotel for sale as is. 24 units. Make offer. 100 Reinken Ave., Belen.”

The hotel’s owner, Albert Villenueve, had no reason to be optimistic in March 1962 when his ad appeared. He had recently filed a lawsuit against the state for damages it had caused by building a new overpass directly in front of his property.

Other businessmen also protested, knowing the overpass would divert traffic and many potential customers. The use of sledgehammers and other powerful construction equipment would cause major damage to older structures like the hotel.

But the protests were to no avail. Businesses and residents on the east side of the Santa Fe Railway’s tracks had long complained about lengthy delays as long trains pulled in and out of Belen’s busy train yards.

In stories that sound much like the situation in Jarales today, people told of being delayed in medical emergencies. In some cases, long trains had to be uncoupled and divided to allow doctors to pass in or out of town.

The state finally built the overpass, despite its impact on accessibility to the hotel and nearby establishments. The road project is said to have been a death sentence to the Kuhn Hotel.

A welcome reprieve

Despite these circumstances, Villeneuve found a person who was willing to buy the hotel “as is.” Recognizing a bargain, Foster Butt made an offer that Villeneuve accepted, closing the deal in 1963. Butt sold the building to Oliver Blais the following year.

If anyone could have breathed new life into the old hotel, it was Blais. A French Canadian by birth, Blais had an adventurous life, starting with his years in the U.S. Army. He served on the Mexican border and reportedly met Pancho Villa face-to-face in Juarez.

On one deployment, his troop marched 500 miles in 21 days, with each soldier carrying backpacks weighing 101 pounds.

Blais also worked in lumber camps in Canada, mining camps in Arizona and on a trolley that ran between El Paso and Juarez. He spent most of his working life as a brakeman for the Santa Fe Railway. After 18 years on the Gallup-Belen line, he had retired in 1964 at the age of 73. But even in retirement, he was a risk-taker, ready for new challenges.

Blais made several changes at the hotel he purchased in 1964, starting with its name. Realizing that the Kuhn name had racist connotations, Blais changed the name to the City Hotel at the height of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. He never discriminated against guests, vowing that anyone could stay at the hotel as long as they could pay their bill.

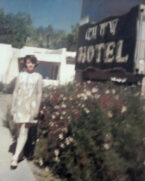

Joan Artiaga outside the City Hotel, c. 1968.

Joan Artiaga was only 17 years old when she went to work for Blais, her maternal grandfather, in the summer of 1968. Her family had just moved to Belen from Chicago. They stayed at the hotel for about a year, with everyone in the family working hard to help out. Joan has vivid memories of her grandfather, the hotel, its clientele and all the work she, her mother and her siblings did.

As through all of its history, most of the hotel’s customers were railroad workers in need of a place to sleep between long shifts in the yards or on train crews. The main things they required were peace and quiet. As a result, Joan remembers a warning sign at the top of the second-story stairs: “Quiet. Men Sleeping.” She also remembers having to take her shoes off to reduce the noise whenever she helped clean the rooms upstairs.

Joan helped wash 30 sets of sheets each week. The sheets were washed in large washing machines, hung out to dry on clotheslines behind the hotel and ironed before they were put back on the beds.

Joan has fond memories of most of her grandfather’s guests. In the summer, they often sat on the front porch, smoking and chewing tobacco. Joan never knew what spittoons were until cleaning them became one of her least favorite responsibilities.

In the winter, guests often sat around a potbelly stove in the hotel’s lobby, telling stories, exchanging jokes or playing checkers, cards and other games on a large table. Few guests made trouble and there were no more cases of intoxicated men running up the stairs and getting shot, as in the old days.

On the rare occasion when Oliver Blais wanted a guest to leave for breaking some infraction, Blais would not evict him. Instead, Joan remembers her grandfather simply read appropriate verses from his Bible until the guest saw the error of his ways and departed on his own accord.

In addition to railroad workers, Joan remembers some other interesting guests who lived more permanently in the hotel’s few apartments. She recalls a man named Mr. Blumensheim who came from Germany and kept lots of books in his room. Like the railroad men, he liked the quiet, especially when he read his books outside on the hotel’s balcony.

Inez Dishman lived in another apartment on the hotel’s second floor. Inez had originally come to the hotel as a chamber maid; she was listed as a 25-year-old chamber maid in the U.S. census of 1930. Fifty-nine by the time Blais bought the business, Inez no longer worked, but seemed to “come with the hotel” in every transition of ownership. It was as if her apartment was part of her unofficial retirement plan.

Tragedy and change

Tragedy struck Oliver Blais on Dec. 4, 1971, when he volunteered to play Santa Claus in Belen’s annual Christmas parade. Dressed as Santa, Blais sat in the back of a fire truck, waving to children in a role he had played many times over the years.

Everything went well until the fire truck’s driver saw smoke in the distance and, forgetting that Blais was seated in the back, picked up speed to get to the blaze. Thrown from the truck, Blais was severely injured. Children who witnessed the accident screamed in horror, seeing Santa Claus bleeding on the street and fearing that he might be dead.

Blais suffered several broken ribs and injuries to his head. He recovered slowly, encouraged by the many get well cards children mailed him in the coming weeks. With Joan’s help, Blais tried to answer each card, but it was just not possible to keep up. Instead, on behalf of Santa, he wrote a letter to the News-Bulletin, assuring local children, “I’m doing fine and will certainly be around to keep this year’s Christmas Eve visits.”

Joan says that her grandfather was never the same after the accident. He sued the Belen Fire Department and the Chamber of Commerce, which had sponsored the parade, for $71,000 to cover medical expenses, loss of wages and punitive damages. His family eventually dropped the case.

No longer able to run the hotel, Blais lived out his life in a house next door. Blais sold the hotel to Roland Kindsvater in 1972. Blais died of cancer in October of that year.

Alan “Dean” Noftsker eventually purchased the hotel, running it as a boarding house and exploring other money-making opportunities. Dean ran a Thieves’ Market in the hotel lobby, selling antiques, jewelry and other items.

Dean made much of the jewelry he sold, using a back room of the hotel for production. He reportedly hired Mexican workers from across the border to help in his jewelry-making enterprise. When border agents occasionally arrived at the hotel, the illegal workers would jump through a trap door in the floor to hide. A rug was thrown over the trap door to conceal its lower chamber. Everyone resurfaced and got back to work as soon as the coast was clear.

Lloyd Sais bought the business when Dean passed away. Hoping to restore the hotel, Lloyd did a lot of work, cleaning up and working on the electricity. He remembers the uphill battle he faced, especially with the old sewer line and aging roof. He was willing to sell by the early 2000s when a woman with strong ties to the building re-entered its colorful history.

Dream of an art center

Heartbroken that her grandfather’s hotel had begun to deteriorate, Joan Artiaga purchased the property in 2003. As its 13th owner, Joan planned to restore the building and convert it into an art center with studios, galleries and places for artists to teach, work and live.

The Kuhn Hotel when it housed the Thieves’ Market in the 1990s

Joan worked hard to fulfill her dream, spending many hours and much of her savings on the project. She and her husband, Pasqual Armijo, made good progress, but faced three main obstacles.

First, as with any old building, the hotel’s roof needed major, very expensive repairs. No matter how much was done to the interior, leaks caused continual damage to the inside. Dealing with the roof and the damage it caused was like taking three steps forward and two steps back.

The next main problem that Joan faced was the Reinken Avenue overpass. The original overpass had been the beginning of the end of the hotel. Two new overpasses built since 1962 have caused additional structural damage and have further reduced access to the property. Complaints to the city have fallen on deaf ears.

Adding insult to injury, Joan has faced thousands of dollars worth of damage caused by vandalism. In her first two years as owner, Joan experienced more than a hundred break-ins, with vandals breaking windows, painting graffiti, leaving beer cans and stealing tools, equipment and pieces of art.

The police patrol the area and have been called to the site countless times, but the hotel’s isolation and the lack of city lighting has made the property more vulnerable than ever. Not even the presence of a caretaker has made a difference.

Odd “guests” appear

Now known by its original name, the Kuhn Hotel has not had registered human guests for decades, but it has had occupants, according to Joan and others, who have witnessed them in one form or another.

Joan says at least four spirits have appeared in various forms throughout the building. One was simply a misty presence on the stairs to the second floor. Another, whom Joan called Henry, was well-dressed and smiling. He looked very much like a man in an old photo of people at the hotel.

Henry clearly appreciated Joan’s efforts to care for the old hotel. Joan says that he often left coins for her around the building. When Joan told Henry he shouldn’t leave her coins, he simply began to leave rings and other jewelry, perhaps left hidden in a cache from Dean’s Thieves’ Market.

The police have responded to reports of intruders in the early morning hours. In one instance, police officers searched the building with their guns drawn, finally cornering the intruder upstairs on the balcony. But somehow the man got away. When Joan showed them the picture of Henry in her old photo, the officers confirmed that he was the man who had mysteriously disappeared when they pursued him onto the balcony.

The presence of ghosts at the hotel has caught the attention of paranormal organizations in the Southwest. Several individuals and groups have visited the building, investigating and reporting that they have detected strong evidence of paranormal activity.

Perhaps disturbed by these investigations, the ghosts have either left or refused to appear since the last paranormal group came by. It seems that even ghosts have a need for privacy or maybe they are tired of all the intruders who have disturbed them. Or they may have simply taken up residence at another haunted old building, the nearby Belen Harvey House Museum.

A new city ordinance

The Belen City Council recently passed a new ordinance in an attempt to deal with many of the old, abandoned buildings in town. Many of these structures have not been kept up, are unsightly and are considered hazardous. The new ordinance warns the owners of these properties to clean them up and make them less dangerous or face heavy fines.

The council’s ordinance makes good sense in the abstract. But in reality, each old building has a unique history and a good reason for its current condition. Yes, some have been wantonly neglected. But other owners have done their best to care for their properties, facing uphill battles that must be considered before prohibitively costly punishments are imposed.

Artiaga is to be admired for all she has done for the Kuhn Hotel. Like Ruth Kuhn, the hotel’s founder, Joan has demonstrated strong independence and courage in the face of adversity. Rather than be accused of neglect and being punished, our community should pitch in to help or at least show patience with her efforts.

Should Joan’s efforts fail and the Kuhn Hotel someday face destruction, many who now criticize will wring their hands and bemoan the loss of yet another building from our historic past. We’ve seen this happen with the old Catholic Church, the Becker-Dalies Store and, most recently, with Sugar Bowl Lanes, lost in a fire.

The Kuhn Hotel is as valuable as any other part of Belen’s downtown historic district. It surely deserves a better fate.

(La Historia del Rio Abajo is a regular column about Valencia County history written by members of the Valencia County Historical Society since 1998.

Richard Melzer, Ph.D

Richard Melzer, Ph.D., is a retired history professor who taught at The University of New Mexico – Valencia campus for more than 35 years. He has served on the board of directors of the Valencia County Historical Society for 30 years; he has severed as the society’s president several times. He has written many books and articles about New Mexico history, including many works on Valencia County, his favorite topic. His newest book, a biography of Casey Luna, will be published soon.

Jim Sloan

Jim Sloan has lived in Belen since he was 2 years old. His passion is the history of Valencia County, and he is the volunteer historian at the Belen Harvey House Museum. He sits on the boards of directors of the Valencia County Historical Society, Belen Historical Properties Review Board and Belen MainStreet Partnership. He has won several awards for his work on local history.

Opinions expressed in this and all columns of La Historia del Rio Abajo are the author’s alone and not necessarily those of the Valencia County Historical Society or any other group or individual.)

(Those interested in joining the Valencia County Historical Society should contact its president, Richard Melzer, at [email protected].)