Baseball fans are familiar with the heroic story of Jackie Robinson’s breaking the color barrier to become the first African American to play in the major leagues. Robinson deserves great credit for not only his outstanding play on the baseball diamond, but also his courageous stamina in facing terrible racial slurs in nearly every city his Brooklyn Dodgers played in during that memorable 1947 season.

It is important to remember Jackie Robinson’s contribution to professional sports. But we must not forget all the other black players who faced similar discrimination as they broke the racial barrier at all stages of their careers and in most parts of the country.

Sad to say, many towns in New Mexico were guilty of mistreating minority ball players in the professional and amateur ranks. The West Texas-New Mexico League, for example, had a rule that no more than four “Negro” players could play on each team in that minor league organization. Latino players from Central America and the Caribbean were counted as Negroes.

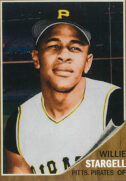

Future Hall of Fame outfielder Wilver “Willie” Stargell played his first professional season for the Roswell Pirates, one of eight teams in the West Texas-New Mexico League. Raised in northern California, Stargell had never experienced deep-seated racial discrimination until that 1959 season.

Treated as equals on the field, 19-year-old Stargell and his fellow black and Latino players excelled in games, but faced segregation in every part of their lives off the field. In his words, “racism was with us every minute of the day.”

Richard Melzer

Segregation was bad in Roswell but worse when the Pirates played on the road. Black players were banned from staying in “white” hotels or motels. As he recalled in his autobiography, Stargell roomed in a black woman’s house when the Pirates played in Artesia. Breeding fish worms inside her house, the woman kept her residence completely dark and boarded up, preventing any kind of air circulation or light.

Stargell and his fellow black and Latino players stayed outside as long as they could until fatigue finally drove them inside to try to sleep in the hot, stale air each night.

Black and Latino players were not allowed to eat in white restaurants in Roswell or elsewhere in the league. Stargell either ate in the segregated restaurants’ kitchens or on the bus if white players took him leftovers from their meals. Stargell eventually brought his own food, although items such as canned Spam did not make for the healthiest diet for young athletes on long bus trips. By the end of the season, Stargell had lost 20 pounds and not even his mother could recognize him when he returned home.

Fans at ball parks were often brutal, crying out racial slurs of all kinds. Stargell was particularly shaken when he heard such slurs coming from the black section of some ballparks.

In his most traumatic incident of the 1959 season, the Pirates were playing in Plainsview, Texas, and Stargell was rooming in a house in the black section of town. The young player was walking across town to the baseball field when a white man jumped out from around a corner and pointed a double-barrel shotgun at him. Pressing the barrels against Stargell’s forehead, the man threatened him, “N–, if you play tonight, I’ll blow your brains out.”

Stargell recognized this incident as the defining moment of his life. He could let this racist tormentor keep him from playing ball and reaching his goal of reaching the big leagues. Or he could defy this bully and refuse to allow hate and prejudice stand in his way.

Stargell chose to play that night and on every other night his name appeared on his manager’s lineup card. By 1962, he had made it to the Pittsburgh Pirates’ major league lineup, where he played for the next 21 years, hitting 475 home runs and becoming one of the most-liked and admired players in the game.

Willie Stargell was not the only athlete to experience discrimination in New Mexico. In 1952, the Albuquerque Dukes had two players ready to become the first black men to play on the team. Apparently, one could not handle the intense pressure. The Dukes released Joe Wiley for “nervousness and lack of experience” just a week after the season began. The other black player, Herbie Simpson, managed to bear the stress and became a star until injuries shortened his baseball career.

Even the Harlem Globetrotters, a world-famous all-black basketball team, faced segregation when they performed in towns such as Roswell in the 1950s and 1960s. Capacity crowds paid good money to see the Globetrotters play ball at the Roswell High School gym, but team members were refused service when they entered local restaurants and other public facilities.

Hispanic players had similar experiences, especially in southeastern New Mexico, a region often called “Little Texas.” Many businesses hung signs in their windows, reading, “No Dogs, Negroes or Mexicans.” Hispanic high school basketball players remember being barred from restaurants, although their fellow white players often refused to eat at such establishments unless their Hispanic friends could eat there, too.

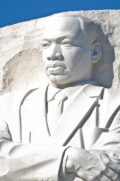

Examples of racism could fill many volumes. One small column on the eve of Martin Luther King Jr. Day is barely adequate to remind us of what has happened in the past. But the best way to ensure that horrible practices in history are not repeated is to study the past, teach inclusiveness and vow never to allow such behavior to occur again.

(The 26th annual celebration and Remembrance of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Community Solidarity and Candlelight Vigil will be held at 6 p.m., Monday, Jan. 21, at the Heart of Belen Gazebo on Main Street and Becker Avenue. The event is sponsored by the city of Belen’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Mutli-Cultural Commission. Please remember and try to abide by our commission’s motto: Living the Dream; Let Freedom Ring; Building Bridges for Unity and Understanding.)

Richard Melzer, guest columnist

Richard Melzer, Ph.D., is a retired history professor who taught at The University of New Mexico–Valencia campus for more than 35 years. He has served on the board of directors of the Valencia County Historical Society for 30 years; he has served as the society’s president several times.

He has written many books and articles about New Mexico history, including many works on Valencia County, his favorite topic. His newest book, a biography of Casey Luna, was published in the spring of 2021.

Those interested in joining the Valencia County Historical Society should contact Dr. Melzer at [email protected].