It’s the second week and things look fairly normal in Berna Chavez’ kindergarten classroom at La Merced Elementary. The students sit on the alphabet rug and listen to her explain the lesson on sight words, keeping mostly fidget free.

The primary difference between Tuesday morning and any other day, is she and all the students are wearing face masks and students sit spaced apart, three to a table.

Directional arrows on the floor in the hallways remind everyone to “keep right.” This is learning in the age of COVID-19.

After months of remote and online classes, students and teachers in the Belen and Los Lunas schools districts returned to campuses last week and began learning in person.

A 22-year education veteran, Chavez said during a “normal” year, teaching kindergartners is a challenge.

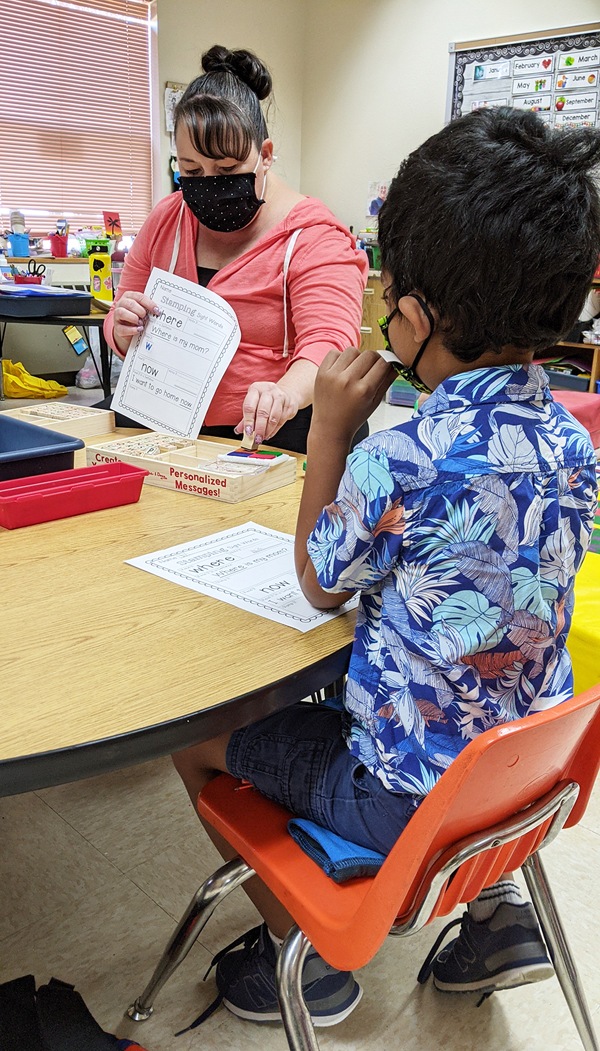

Julia M. Dendinger | News-Bulletin photo

La Merced Elementary kindergarten teacher Berna Chavez demonstrates how to stamp sight words on a worksheet during a morning lesson. Like most teachers around the state, Chavez is readjusting to in-person teaching after months of remote, online lessons.

“They have to learn things like walking in line. They are new and getting used to being in a structured environment,” Chavez said. “They get used to it pretty quick and after they are taught the procedures, they get better at ‘how to school.’”

BCS started this school year in the hybrid model, where half the students were in the classroom two days a week while the rest were learning remotely. The two halves alternated so all students had two days of in-person learning.

When COVID-19 cases spiked in November, the district decided to shift to fully remote learning, which created the challenge of the amount of age-appropriate screen time, Chavez said.

“They could only take so much before they got fidgety,” she said.

Kindergartners were online for an hour and 15 minutes in the morning, then 45 minutes in the afternoon, which included special subject classes such as art or PE.

“Others had intervention time and were getting almost four hours of screen time, which is kind of a lot,” she said.

Often while teaching remotely, Chavez said she felt like she was putting on a show, using a Bluetooth microphone to be heard and a giant hand-shaped clapper to get students attention. There were also more expectations of parents in terms of day-to-day learning, she said.

“Especially for the younger ones. Parents would have to log them on, reconnect them. Parents would have to submit their work,” she said. “For some families, I know we saw they didn’t have a lot of familiarity with the technology, so that was another challenge.”

About 40 kindergartners returned to La Merced on April 6 while seven remained in remote learning, Chavez said. When the district was in the hybrid model, two of the school’s three kindergarten teachers taught students in-person while the third taught the students who were learning remotely.

Now back to in-person and still having to offer remote lessons, Chavez said the remote teacher stuck with that task, and she and the other teacher created schedules that would let them cover for her during her intervention time with students.

“We all support her throughout the day; we thought it would be easier that way,” she said. “She was actually able to go through the curriculum a little faster since she was on four days a week, and she kept them there and progressing.”

Recently, three of Chavez’ students switched to the remote teacher while three remote students joined her in person class.

“We switch so we can target kids who might be struggling a little more. That way we won’t have to focus on so many levels. My class has different levels but I’m in the classroom all the time,” she said.

Chavez called this year different and frustrating because of the way things kept changing so rapidly.

“It wasn’t our administration making the changes. It was not a Belen thing. It was coming from the state. They kept making radical changes on the fly and expecting the districts to make all the changes,” she said. “One week we couldn’t mix cohorts, a week later everybody can come.

“We would put in all this work and hours for nothing. It was frustrating but I think (the administration) and superintendent have done a great job managing that and taking the brunt force of it.”

Chavez understood the constant changes and current situation was frustrating for parents as well, and asked they give teachers a chance to be heard.

“Don’t assume they are not doing their job. Yes, ask questions, ask what the problem is and let the teacher be heard. Hear what they have to say,” she said. “I feel lucky at La Merced to have the principal we have who trusts us to do what is in the best interest of the kids, which I think we’ve done very well.”

While Chavez has more than two decades of experience, Jesse Moya, a first-year senior English teacher at Los Lunas High School, describes himself “as green as can be.”

“The biggest challenge is that I’m not just speaking to a computer anymore; I have to speak to the computer and three or four students sitting in desks right now,” said Moya.

Before making the career move to education, Moya worked for five years as a journalist at the Taos News covering government, education and veterans affairs.

“It was strange at first, I’m not going to lie, going from one industry to a completely different career path is very, very strange,” he said. “The lingo is different, the hours are different, but, above all the strangest and hardest part was switching from being media-minded to being educator minded.”

Although he had a small learning curve, he said overall his experience has been positive due to a good group of motivated students and educator colleagues who have helped him through the transition.

Moya began the semester in Taos, Zooming in to teach his students, who lived three hours away. As the semester went on, he said it was his goal to create an understanding with the students that he wanted to help them in their path to graduation.

“Building that understanding that I am more than just a teacher and they are more than just students,” he said. “I feel like that has really helped me and them throughout this year.”

Although online for most the year, Moya said he made an effort to learn about his students and encouraged them to show their faces for the first five minutes of class so he could know they were there and ready to learn.

As classes transitioned from online to an in-person environment, Moya said some of his students made a “180 change” in both attitude towards class and participation. Still, Moya said most of his students remained at home, with less than 10 percent returning physically to the school.

A graduate of Valencia High School, Moya said even while working as a journalist, friends and co-workers always commented on his teaching abilities. When the opportunity came to teach where he grew up, Moya said he was ready to take on the challenge.

“I always felt like I wanted to come back to this community. This community did so much for me when I was growing up and I want to return that favor now that I am grown up,” Moya said. “Even if it’s as small as teaching English to a group of students who really feel disconnected from school itself. I just want to help.”