(La Historia del Rio Abajo is a regular column about Valencia County history written by members of the Valencia County Historical Society. The author of this month’s column is John Taylor, a retired engineer from Sandia National Laboratories and board member of the Valencia County Historical Society. He is the author or co-author of 21 books on New Mexico history, including “Murder, Mystery, and Mayhem in the Rio Abajo,” “A River Runs through Us,” “Tragic Trails and Enchanted Journeys,” “Mountains, Mesas, and Memories,” “Years Gone by in the Rio Abajo,” and “History Surrounds Us,” all co-edited with Dr. Richard Melzer. Opinions expressed in this and all columns of La Historia del Rio Abajo are the author’s only and not necessarily those of the Valencia County Historical Society or any other group or individual.)

A dwindling number of us remember the early 1960s. The Cuban Missile Crisis brought the Cold War into sharp focus: one of our most popular presidents was assassinated in Dallas; school children were taught to duck and cover; and, as a teenager in a small California desert town, I was hired to help a family friend build a fallout shelter next to his home.

Northern bunker under construction in August 1963.

New Mexico was not immune to these concerns. Some obvious targets for enemy missiles or bombs were Sandia Laboratories and Los Alamos, the original home of the U.S. nuclear weapon program, as well as Kirtland Air Force Base, home to several important Air Force facilities. Other important military facilities were scattered throughout the state.

Because of the importance of maintaining reliable communications with the nuclear activities at Kirtland, Sandia, Los Alamos, and other locations, particularly during times of crisis, the Headquarters of Field Command of the Defense Atomic Support Agency (DASA), whose headquarters were located on Kirtland Air Force Base, issued General Order 22.

This order directed the construction of backup communication facilities west of Belen on 500 acres of government-owned land that was being leased for grazing cattle by Malcolm “Buddy” Majors, a Socorro rancher. These facilities were known as the Belen Communication Transmitter Sites.

Post-construction image of the northern Belen bunker in August 1963.

Two bunkers were constructed, one near the airport and the other about two miles south of the airport. The chosen locations were a “safe” distance from what were thought to be the primary targets elsewhere in the state. The press release for the Belen Communication Site stated that the equipment in these bunkers was designed to replace existing radio equipment at Sandia Base and to “take advantage of the terrain characteristics and to isolate the equipment from noise-producing electrical installations in Albuquerque’s commercial and industrial areas.”

Constructing the bunkers

Construction began in late 1963 and was conducted by several independent contractors to ensure no one individual or organization had full knowledge of the layout and capabilities of the facilities. The bunkers were laid out southwest to northeast with their doors facing southwest.

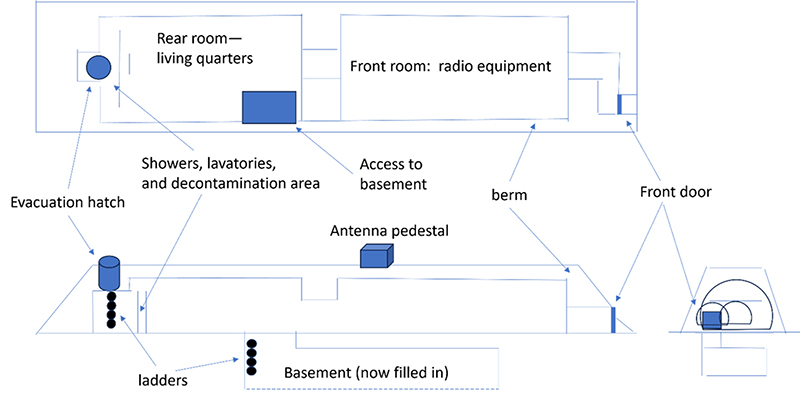

Initially, a large trench was dug, and a thick pad of concrete was poured to support radio equipment that was to be installed in the basement. Access to the basement in the southern bunker was provided via a ladder. In addition to the ladder, the northern bunker had an outside basement access.

After the basement was completed, the top floor was poured, and the upper portion of the facility was divided into two main sections. One section was used for radio equipment, and the other section was used as living quarters for that portion of the crew that was on watch. It included a sleeping area, a shower that doubled as a decontamination unit in the case of nuclear attack, and a bathroom connected to an outdoor septic system.

Google Earth view of the southern Belen bunker in 2023.

Once the concrete was poured, a set of Quonset-type structures were placed on top. The two main rooms were 16 feet from floor to ceiling and there were 12-foot floor-to-ceiling steel structures for the entrance, the passage between the front and rear rooms, and the entrance to the decontamination and evacuation access area.

The bunkers were clearly constructed to be blast resistant. The front doors were set off-center with a blast wall between them and the front room, and there appear to have been shock mitigation tubes installed around the exterior. A fence surrounded the berm, and the entrance was manned 24/7. A roving patrol monitored the perimeter.

In addition to the main entrance, there was an “escape hatch” in the rear of the bunker that permitted emergency egress, as well as access via an installed ladder to an antenna complex on top of the berm. A water tank was installed outside the bunkers with a pipe that ran from Belen, and electricity was provided from the city with on-site backup generators in case of emergency.

Once the construction had been completed, the entire structure was covered with a dirt berm. The images of the northern bunker show piles of dirt on both sides of the bunker. This may have been dirt that was excavated when the basements were dug and was subsequently used to construct the berms.

The “skirt” of the berm was approximately 8 feet from the outside edges of the Quonset huts. The top berm was between 3- and 4-feet thick. The completed bunkers measured about 200 feet from southwest to northeast, about 40 feet between the edges of the berm’s “skirt,” and about 24 feet from ground level to the top of the berm.

The two structures were not identical

Although both bunkers had the same external configuration, a more detailed examination of the two shows some significant differences. We do not have construction photos of the southern bunker, but, as shown in the as-built elevations below, the front room of the southern bunker was the longer of the two and was apparently used to operate the communication equipment in the basement. The crew quarters were in the rear section of the southern structure.

Entrance to the southern Belen bunker.

As shown in the August 1963 construction photo, the northern bunker has reversed this configuration with the shorter section, presumably the crew living quarters, in the front section and the larger equipment section in the rear. Both installations have a vertical evacuation hatch at the rear of the facility, but the northern bunker has what appears to be a basement entrance with stairs on the southern side.

In addition, there are five large ductwork installations on the north side of the northern bunker, which are not present in the southern bunker. The outlets from these ducts, shown in the post-construction photo, appear to be closures of some sort, perhaps a form of shutters.

The T-shaped pole on the back of the northern structure is a telephone pole that is not directly associated with the radio equipment inside the bunker. The tank and associated piping midway down the side of the berm on the northern bunker may be cooling water for the electronic equipment and/or water for the living area in the front of the structure. The wheeled vehicle to the left of the entrance may be a portable generator or a welding machine associated with the ongoing construction.

Elevations showing the basic layout of the southern bunker.

The function of the ducts and “shutters” on the north side of the northern bunker’s berm is not clear. They do not appear on the inside of the structure of the southern bunker.

One explanation may be ventilation for heat-generating equipment. In any case, it appears that the two bunkers were designed to perform different aspects of the communication tasks and were probably designed to operate in tandem as a single backup communication facility.

(Editor’s note: The second part of this article will publish on Thursday, Nov. 30.)